There’s Something About Typhoid Mary

How do hamburgers connect to typhoid fever? Follow as we discuss turn-of-the 20th century meat industry, Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, Theodore Roosevelt and creation of the FDA, Salmonella enterica typhii, typhoid fever, and Typhoid Mary.

Show Notes

(0:03 – 0:23)

I’m a little bit concerned about what my 3 and 5 year old kids will remember. Why? So my dad’s a really good cook, especially with the grill. And so when it was my turn to be the grill master, I went and bought a grill, I bought those really big tongs, and then I also bought a pair of New Balance sneakers.

(0:26 – 0:44)

Oh, why? And then I decided to start with steak, because you can undercook it and nobody’s going to get sick. Alright. But I go to these birthday parties and the dads are serving hamburgers, and I’m terrified of hamburgers, because if you undercook those, everybody gets sick.

(0:45 – 1:11)

Yeah, just last week there was a report of a case of typhoid fever that occurred just up the road in McKinney, Texas, in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, and then after that, a student in an elementary school in a neighboring suburb ended up testing positive for typhoid. Yeah, so I don’t want to be that guy. And since I did some microbiology, if I got my friends and family sick, that would just be, like, extra that guy.

(1:11 – 1:21)

I don’t think I’d, like, let you live it down if you got, like, anyone sick with your cooking. I would definitely hold it against you for the rest of your life. Yeah, it would probably be called the Uncredible Burger.

(1:21 – 1:46)

I’m Dr. Dustin Edwards, and I’m here all week. Oh my god. And I’m Faith Cox.

Welcome to Germomics, where we go to, be, from, a, in the most roundabout way, a mix of microbiology and history. In this series, we connect different aspects of modern life and society to microbes through seemingly unconnected natural events, discoveries, and inventions. So how do hamburgers connect to typhoid? Let’s find out.

(1:49 – 2:17)

The hamburger was supposedly invented in 1900 in New Haven, Connecticut, which is the same place where Yale University is, and it was made by a Danish immigrant named Louis Lasson. This is, of course, disputed in that the very word hamburger can be derived from Hamburg, Germany. The White Castle chain has traced the origins of the word hamburger to Germany, but that version also contained a fried egg on it.

(2:17 – 2:35)

To muddy this up even more, there is a Hamburg, New York, which claims that the hamburger was invented there at a county fair. And these list of origin stories just go on and on. Nonetheless, though, the hamburger was a feature at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, and did spread out from there.

(2:36 – 2:50)

Shortly after the hamburger was featured at the 1904 World’s Fair, The Jungle was released by Upton Sinclair. So the book was initially released in 1906. However, he published it before that as a series of articles in 1905.

(2:51 – 2:58)

The book follows an immigrant in Chicago. There he works at a slaughterhouse. Working conditions were harsh, and he struggled to support himself and his family.

(2:58 – 3:13)

The novel follows him as he struggles through life in America. If you ever wanted to read a series of really unfortunate events, read The Jungle. Yeah, so it was written to kind of expose how hard it could be to be an immigrant in America at the time.

(3:13 – 3:36)

But what the public paid attention to was the health violations and unsanitary practices in the meatpacking industry. That wasn’t what Sinclair intended, and he actually said, I aimed at the public’s heart and by accident I hit it in the stomach. So the general public was actually so upset over the unsanitary practices depicted in the book that it led to reforms such as the Meat Inspection Act.

(3:37 – 4:04)

Sinclair actually worked incognito in the meatpacking industry for seven weeks to gather the information that he used to depict the industry in the book. The president at the time didn’t think the industry was as bad as Sinclair was making it out to be in the book and thought he was being hyperbolic and even called Sinclair a crackpot. So then the president at the time sent the labor commissioner and a social worker to go investigate the conditions of the industry in Chicago.

(4:04 – 4:20)

And the owners of the plants actually had their workers like very thoroughly clean the plants in advance. So hopefully the commissioner and the social worker wouldn’t be disgusted. But it was so badly off that when they got there after being cleaned, it was they were still disgusted by the conditions.

(4:21 – 4:36)

Yeah, there was initially just going to merely publish a report. But the president was so appalled that he sent it directly to Congress. The labor commissioner testified before Congress about the conditions and said there was a need for legislation regarding the industry.

(4:37 – 4:58)

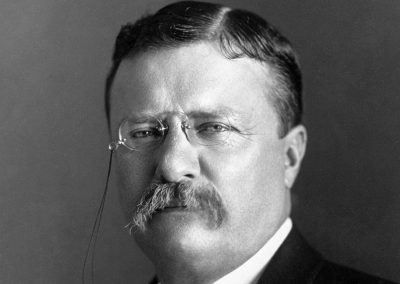

The report and testimony, along with public pressure, led to the passing of the Meat Inspection Act, the Pure Food and Drug Act, and established the Bureau of Chemistry, which was later renamed to be the Food and Drug Administration that we know today. All of this done by President Theodore Roosevelt. So Teddy Roosevelt was a complete badass.

(4:59 – 5:09)

Best president ever. He was the 26th president of the United States. And we could honestly do like a whole season about the different pathways you could take off Teddy Roosevelt by himself.

(5:09 – 5:22)

He did so many things. You know, when I lived in D.C., I would go to the National Mall fairly often. And you would kind of wander around there and you look at the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Memorial and the Jefferson Memorial.

(5:22 – 5:35)

And there was no Teddy Roosevelt Memorial. There was a other Roosevelt Memorial, but not a Teddy Roosevelt Memorial. And then one day I realized that they actually named an entire island after him.

(5:35 – 5:43)

And no cars were allowed. So you had to like walk or take a bicycle over this bridge to go and look around. And it was like a little wildlife reserve.

(5:44 – 5:59)

That’s such a nice little thing for him. Yes, and they had a modest statue of him in the middle of the island. Aww.

That’s actually really nice. So Teddy Roosevelt had like a brief little stint as a cowboy. He was a naturalist.

(5:59 – 6:08)

That’s why the island’s like super interesting. And he actually learned the basics of taxidermy and was a published ornithologist. He wrote a book called The Naval War of 1812.

(6:08 – 6:19)

That was about the Navy in the War of 1812. He was the assistant secretary of the Navy under President William McKinley. He led the Rough Riders, which were a volunteer cavalry during the Spanish-American War.

(6:19 – 6:32)

And with that, he won a Medal of Honor, the highest award that the U.S. military can award for his efforts in leading them into a specific battle. He was the governor of New York. He was the vice president for President William McKinley.

(6:33 – 6:43)

And then he was the president after McKinley’s assassination. And as president, he made conservation a high priority and established new parks. He began the construction of the Panama Canal.

(6:43 – 7:06)

He even won the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts regarding the Treaty of Portsmouth, which ended the 1904-1905 Russo-Japanese War. And then when he was about to give a speech, just as a separate event, when he was about to give a speech, someone shot him in the chest as an assassination attempt. And then he decided to finish his hour-long speech before going to the hospital.

(7:07 – 7:17)

Apparently, he realized when he didn’t start coughing up blood that nothing vital was hit. So he decided to do a speech. He explored the Amazon and even has a river named after him now.

(7:17 – 7:33)

I am simultaneously in awe of Teddy Roosevelt and deathly afraid of the sheer amount of power a man like that has. So he did a lot of really cool things. And like I said, we could do a whole season on Pathways just about Teddy Roosevelt.

(7:34 – 7:44)

But we’re going to focus on the beginning of his life. As a child, Roosevelt had a very severe asthma. And he realized while on a hike with his father that strenuous exercise lessened his asthma.

(7:44 – 7:56)

So he decided to beef up. So because of his asthma and just for some general reason, he was very sickly as a child. And at the age of seven, he developed an interest in zoology after seeing a dead seal at a local market.

(7:56 – 8:05)

He then acquired the seal’s head and formed with his cousins, the Roosevelt Museum of Natural History. Wait, wait, wait, wait, wait. You just, wait.

(8:06 – 8:18)

You just asked somebody for like. The exact manner in which he acquired the seal head. I didn’t find a citation for, so I just know he had it.

(8:19 – 8:33)

He got it. And then he made the Roosevelt Museum of Natural History with his cousins. From there, he learned the basics of taxidermy and filled his museum with just specimens that he collected.

(8:34 – 8:52)

He would study the animals and prepare them to be viewed and then even record his observations of insects. It was actually when he was 11 years old while he was hiking that he realized the exercise helped with his asthma. And then after being manhandled by a couple of older boys on a trip, he decided to learn how to box.

(8:53 – 8:59)

And this is the point in time that he got like real beefy. He was like a stocky man if you look at him. He could win a fight.

(9:00 – 9:12)

After that, he attended Harvard where he did well in his sciences, philosophy and rhetoric courses. But he struggled in language courses like Greek and Latin. He was really involved at Harvard.

(9:13 – 9:27)

He was in like several clubs and a fraternity even. After that, he attended law school and he began writing the Naval War of 1812 while at Harvard. And on his 22nd birthday, he married Alice Hathaway Lee.

(9:27 – 9:46)

They had a daughter, Alice Lee Roosevelt, that was born on February 12th, 1884. Unfortunately, two days after giving birth, on Valentine’s Day, his wife died from kidney failure. It was kind of out of nowhere because all of her symptoms were masked by her pregnancy.

(9:47 – 9:58)

Earlier in the day, his mother also died. She died of typhoid fever. Both Roosevelt’s mom and his wife died at their house on Valentine’s Day.

(9:58 – 10:23)

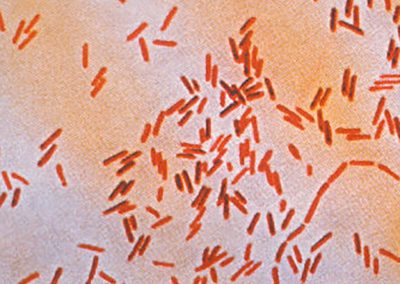

In his diary for that day, Roosevelt just wrote a large X over the page followed by The light has gone out of my life. Typhoid fever is caused by a bacteria called Salmonella enterica, serotype Typhi. And to try to visualize what this bacteria looks like, it’s very similar looking to me as Vienna sausages, except also fuzzy.

(10:23 – 10:35)

So a little bit like if it was a stuffed animal too. And they have flagella, multiple. If you’ve ever seen those videos of people stabbing spaghetti noodles through a hot dog and then boiling them, they have flagella kind of like that.

(10:36 – 11:02)

A lot of Salmonella infections are self-limiting, but Salmonella typhi is more severe. So severe that a paper from 2006 indicated that typhoid fever may have been a contributing factor to the plague of Athens, which was a plague that took out one third of Greece’s population, based on the examination of ancient dental pulp. Most people in the US with typhoid fever become infected while traveling outside of the country.

(11:03 – 11:20)

It’s not endemic here, but you can get it in other countries and then bring it back. Worldwide, there are about 22 million infections per year. However, in the US, there are about 350 cases per year, with most of those infections being acquired in India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan.

(11:22 – 11:34)

Salmonella typhi is shed in the feces of people and no animals are known to carry it. This is a major reason for hand washing. A person acquires Salmonella typhi by eating contaminated food or water.

(11:35 – 11:48)

So the fecal-oral route. The bacterium itself is a gram-negative rod-shaped facultative anaerobe. Gram-negative, meaning it has an inner membrane, a cell wall, and then an outer membrane.

(11:49 – 12:02)

And facultative, meaning it can live in an oxygenated or a non-oxygenated environment. It’s only known to infect humans. So not only is there not an animal reservoir, but it’s actually only infecting people.

(12:04 – 12:29)

It initially enters the body fecal-orally and propagates in the intestinal tract and spreads through the peripheral lymphatic system, which is the portion of the immune system that your B cells, which make antibodies, and your T cells, which help train your B cells, come from. These also include organs such as the spleen or the Peyer’s patches. The Peyer’s patches are little bits of lymphatic tissue in the ileum region of the small intestine.

(12:30 – 12:51)

The ileum is in the final third of the small intestines before it becomes the large intestines. And its function is to help absorb nutrients, such as like vitamins, after you have digested them in your stomach. From there, the bacteria are able to infect macrophages, which are one of the main phagocytic cells of the immune system.

(12:51 – 13:14)

Phagocytic cells are cells that engulf pathogens and then degrade the pathogens as waste. However, salmonella gets inside of the macrophages and then is able to hide from the host’s immune system and they don’t get degraded. And then the bacterium actually replicates inside of the infected cell and then they’re released and they kill the cell in the process.

(13:14 – 13:36)

So they take what’s normally a really helpful cell, one of the main helpful cells for your immune system, and engulfing pathogens and they use it as a home to populate in. After that, they can be excreted and they can recirculate in the body or go into the gallbladder where like persistent infections tend to occur. Or they can be excreted in the feces.

(13:37 – 13:50)

And the ones that are excreted in the feces are the ones that are shed into the environment to infect new hosts. However, if they recirculate in the body, that’s what causes a systemic infection. So an infection throughout the whole body and not in a localized region.

(13:50 – 14:12)

Like if you had like an infected ingrown toenail, that’s different than a systemic infection. Like some other fecal-oral diseases, salmonella typhi requires a higher infectious dose, somewhere between 10 to the 3rd and 10 to the 6th bacteria, because it lacks acid tolerance. So it has to get through the pH of the stomach, which is about 1 to 2, and then establish infection.

(14:13 – 14:31)

So during that process, a lot of the bacteria die in the stomach and don’t make it to the small intestine. After that, symptoms may present somewhere between 1 to 14 days after infection. And those infected can be classified as symptomatic or asymptomatic, which is when someone doesn’t have symptoms.

(14:32 – 15:17)

Symptoms can vary from a very mild illness with a low-grade fever, so 100 degrees Fahrenheit to 102, to a much more severe presentation. Patients can have headaches, fatigue, malaise, which is like a general feeling of unwellness, loss of appetite, coughs, constipation, and a skin rash or rose spot, so just like little speckled red spots on the body. It can also have much more fatal complications, such as intestinal perforations, which are holes in the intestines, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, which is internal bleeding in your intestines, encephalitis, which is just a general term for brain damage caused by a disease, or cranial neuritis, which is inflammation of the cranial nerve.

(15:19 – 15:35)

Salmonella typhi causes these symptoms through the use of several virulence factors. After about two weeks of symptoms is when the patients may start to have more serious complications, if left untreated. They may have that gastrointestinal bleeding, the intestinal perforation, or typhoid encephalopathy.

(15:36 – 16:07)

The gastrointestinal bleeding is the result of the Peyer’s patches being degraded in the encephalopathy, and other neurological symptoms are what lead to the name typhoid fever, which originally comes from the Greek word typhos, meaning smoke, and that refers to how the patients can kind of get apathetic and have a lot of confusion, and they’re delirious. This specific symptom is associated with a high mortality rate, even if they start receiving treatment. If you have active typhoid fever, the treatment for that is just antibiotics.

(16:08 – 16:28)

However, if you know in advance that you’re going to an endemic area, then it’s recommended that you get one of the vaccines that’s offered. For our science and society message, we want to talk about how we treat infected people. Despite societal progress, there still remains a stigma against people who are known to be infected with a virus or bacteria or parasite.

(16:29 – 16:46)

While I was at the NIH, we had a visitor to the lab named Ben Banks. Ben is remarkable in that he has probably lived with HIV longer than anyone else. In 1981, when he was just a baby, only two years old, he had kidney cancer, and it spread to both of his lungs.

(16:47 – 17:06)

He ended up receiving blood transfusions during treatment to help save his life, and he acquired the virus that way. But he didn’t know yet. It wasn’t until he went in for his 10-year cancer-free checkup, something he was celebrating at the age of 12, that he tested positive for HIV.

(17:07 – 17:32)

Now, this story actually has a happy ending, but my heart always breaks when I think of how unfair life is for some people, especially with kids. The good news for Ben and for us is that he never progressed to AIDS and now leads about as normal of a life as possible. He graduated from college, he got married, and then a few years ago, they had a baby girl together.

(17:33 – 18:00)

Ben Banks is an ambassador for the Elizabeth Glasser Pediatric AIDS Foundation, and I encourage everyone to learn more about his story and his message, which is breaking down barriers and stigma towards those living with HIV. Someone else we can talk about is Mary Mallon, who was also known as Typhoid Mary. She was called the most dangerous woman in America, and while she’s a household name, it’s important to remember what her case was all about and what happened later in her life.

(18:00 – 18:15)

Mary immigrated to the U.S. as a teenager from Ireland. In 1900-1907, she was employed as a cook for seven different families in New York City. Within the first two weeks on the job, the family started to develop typhoid fever.

(18:16 – 18:39)

In all, she infected at least 50 people with Salmonella typhi, and three of those people died. Mary was different in that she was an asymptomatic carrier, which is a person who is infected but never develops symptoms or becomes sick, and hers was the first case in which a healthy carrier was described and written about. Her condition was discovered and characterized by George Soper.

(18:39 – 19:18)

At first, he explained his idea and then asked for her urine and stool samples, and remember, we are at the end of the Victorian era, so she, of course, was quite upset by the allegation and adamant in refusing to give him any bodily samples, which, from her point of view, she was absolutely healthy, so it made no sense to her that she would be infected by the bacteria. She was eventually arrested, though, and while in prison, was forced to give urine and stool samples, which are determined to be positive for Salmonella typhi. She was then sent to be quarantined at Riverside Hospital on North Brother Island in the East River, and she was held there for two years.

(19:19 – 19:44)

During that time, 120 out of 163 stool samples tested positive, and the newspapers went crazy over this story and forever branded her Typhoid Mary. She was released from prison with explicit instructions to not work another job that involved cooking, and the city government even helped her get work that didn’t involve cooking. She was employed as a laundress, which paid less than what she was making before.

(19:45 – 20:02)

In public, she was shunned and became a household name for anyone, knowingly or not, who spread a disease. It’s really easy to blame the media on this one. She eventually changed her name to Mary Brown, and then started to work in a kitchen again under her new identity at a hospital.

(20:03 – 20:19)

25 people got sick and two died. After that, she was arrested again and spent the rest of her life in quarantine on North Brother Island for almost 25 years. So, we have this person who has no symptoms that is quarantined on a small island for a quarter century.

(20:20 – 20:28)

Should she have continued to work in a kitchen? No. But I’m willing to place the blame on the media for backing her into a corner. And here’s the kicker.

(20:29 – 20:49)

During her quarantine, several other asymptomatic caries were discovered, so why was she singled out against, like, everyone else? She once wrote that she was just a peep show for everyone. This could be due to the media backing her into a corner and the public’s morbid interest in her. Needless to say, new infections happen every day.

(20:49 – 21:04)

In extreme cases, quarantines are still a strategy to try to contain a disease. I think, though, that as a society, we need to treat people like people, no matter what may be inside of them. Yeah, I think that’s really important.

(21:04 – 21:41)

I know sometimes people, like, won’t get tested for a disease because they’re afraid of the stigma attached to it, and that’s just harmful to themselves and society, and it’s horrible that we, like, make people feel that way. Just as a quick recap, we talked about hamburgers as a processed meat and how the meat processing industry was previously unlegislated in the beginning of the 1900s. And then the public outrage caused by The Jungle by Upton Sinclair led to the passage of several legislations about food regulation by President Theodore Roosevelt, whose mother died of typhoid fever, which is spread in unsanitary conditions via the fecal-oral route.

(21:41 – 22:09)

And typhoid Mary and the stigma placed by society on those unfortunate to become infected. Thank you for listening to episode 6, There’s Something About Typhoid Mary. Show notes, transcripts, citations, and social media links are available on our website at germomics.com. What do you think kids remember when they’re young? Like, in general? Or like, at what age do they start remembering? So I went to a fall festival yesterday, and it was like 100 degrees outside.

(22:10 – 22:14)

Oh, gross. Yeah, everybody was miserable. And, well, they were having fun.

(22:15 – 22:39)

But had the weather been more fall-like, I think a lot of the activities they had there would have been more enjoyable. But they had this very large slide that was set up to resemble a snowy hill that you would take a sled down. Except it’s 100 degrees outside, right? And so they have this plastic carpet that covers this big slide.

(22:40 – 22:48)

And then you use an inner tube to come down on. And so my kids say, hey, we really like sliding. I think we should go on the slide.

(22:48 – 22:56)

I’m like, okay. And so we go there, and I take the oldest one, who’s 5, and we go up to this top. And it’s actually quite the distance up.

(22:57 – 23:09)

I’m going to guess like 30 or 40 feet. And the slide’s several hundred feet. Okay, yeah, that’s a lot.

That’s like a large slide. Yeah, at least a couple hundred feet. And then they have like a bump so you can get a little bit of air when you hit it.

(23:10 – 23:22)

And so the 5-year-old goes down and has a great time. And then I’m helping her go back up again. And then my wife and the 2-year-old, I mean, they were off doing their own thing, I thought.

(23:23 – 23:37)

Except I was going up the ramp to the top of the slide. And then I see the 3-year-old coming down. And everything went into slow motion when she hit the bump, right? So I look over, and the inner tube’s like slightly turning.

(23:38 – 23:59)

And I see her big open eyes slam shut and her mouth wide open in a silent scream. And she actually got some good air and lands and slides all the way down to the very, very end of the slide to the attendant, which was something. I get up there at the top, though, and I slide back down.

(24:00 – 24:17)

And I got about 2 inches of air and only went about a foot and a half down, further down the slide. And then I had to do like a walk of shame down to the bottom. And then my kid was like, I think there was like a turning point.

(24:17 – 24:26)

Either the day was going to be a really good memory or a very bad memory. Because then she just looked at me and said, we’re going to go get ice cream now. Nice.

(24:26 – 24:30)

So that’s what we did. I think she had a decent memory.

Credits

Written and performed by Dr. Dustin Edwards and Faith Cox

Music from https://filmmusic.io

“Poppers and Prosecco” by Kevin MacLeod (https://incompetech.com);

license CC BY 4.0

Images from

Theodore Roosevelt © Library of Congress; public domain

Salmonella enterica typhi © CDC; public domain