Antitoxin Togo, Please

What do blue jeans have to do with diphtheria antitoxin and the 1925 Serum Run to Nome? Follow the journey from Levi Strauss and the Gold Rush to the 1925 serum run, where sled dogs raced to deliver life-saving antitoxin. Timeless fashion and infectious diseases might seem like an unlikely pairing, but history has a way of weaving together the unexpected.

A Flood of Fortune Seekers: The California Gold Rush

The Discovery That Changed Everything

In January 1848, a carpenter named James W. Marshall inspected a sawmill he was building for John Sutter in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Walking near the mill’s water channel, he noticed something glittering in the sunlight—small, golden flakes caught in the riverbed.

Marshall and Sutter initially tried to keep the discovery secret, fearing it would disrupt their operations. But words spread faster than they could contain. Within months, rumors of gold reached the East Coast, and by 1849, an estimated 90,000 prospectors had descended upon California in what became known as the Gold Rush.

The promise of instant wealth proved irresistible, fueling one of the largest voluntary migrations in world history. Men and women from every continent uprooted their lives and set out for California, lured by the hope that they, too, could strike it rich.

But the journey west was treacherous and unforgiving for most. Many never reached the goldfields.

The Massive Migration of the ‘49ers

Between 1848 and 1855, over 300,000 people from all over the world arrived in California. These hopeful adventurers became known as the “Forty-Niners” after the peak migration year 1849.

The Harrowing Journey to California

At first, only a handful of lucky prospectors found easy-to-access gold, but the dream of instant wealth fueled an even bigger wave of migration. People came from four primary routes, each with extreme risks and hardships.

- By Land: The Oregon and California Trails

Many migrants traveled overland in wagon trains, following the Oregon Trail or California Trail. These journeys, stretching over 2,000 miles, took four to six months and were dangerous. Harsh weather, starvation, disease, and attacks by bandits were typical. Thousands perished before ever reaching California. - By Ship: The Cape Horn Route

Those who could afford it traveled by sailing around South America’s Cape Horn. This route was safer but expensive, requiring four to eight months at sea. Storms, food shortages, and scurvy claimed many lives along the way. - By Ship and Land: The Panama Shortcut

Some tried to shorten their travel time by sailing to Panama, crossing disease-ridden jungles, and catching another ship on the Pacific coast. This was the fastest route, but malaria and yellow fever decimated many travelers before they reached California. - From Across the Globe

- Europeans—thousands of Irish, German, and Italian immigrants arrived in the U.S., escaping poverty, famine, and political instability.

- Chinese migrants—by 1852, over 25,000 Chinese immigrants had reached California. They established some of the first Chinatowns in America but faced severe discrimination and violence.

- Latin Americans—miners from Mexico, Chile, and Peru brought advanced mining techniques, but many were later driven out as xenophobia increased.

The Transformation of San Francisco

Before the Gold Rush, San Francisco was a quiet, sleepy settlement with around 1,000 residents. By 1852, it had exploded into a bustling city with over 36,000 residents, making it one of the fastest-growing cities in the world at the time.

The Gold Rush Boom and Its Chaotic Consequences

As thousands of fortune-seekers poured into California, San Francisco became the epicenter of the Gold Rush economy. But the rapid expansion came with serious problems:

- Overcrowding – Miners arrived faster than housing could be built, forcing many to live in tents, makeshift huts, or the streets.

- Lawlessness – The city lacked a police force, and crime ran rampant. Robberies, brawls, and vigilante justice were common.

- Fire Hazards – San Francisco’s hastily constructed wooden buildings were highly flammable, and fires frequently burned entire neighborhoods to the ground.

- Inflation and High Prices—Basic goods became outrageously expensive due to demand. A single egg could cost $1 (equivalent to $30 today), while a shovel could cost as much as $1,000 in modern currency.

Despite the chaos, San Francisco quickly became a permanent economic powerhouse. While some prospectors struck gold, the real money was made by entrepreneurs and merchants who supplied them.

Who Really Got Rich? The Rise of Entrepreneurs

The popular image of the Gold Rush is that of grizzled miners striking it rich overnight, but in reality, the true winners were those who sold goods and services to miners.

- Merchants selling mining tools, food, and clothing could charge exorbitant prices.

- Saloons, gambling halls, and hotels profited from weary miners seeking food, entertainment, and rest.

- Blacksmiths, carpenters, and tailors saw constant demand for their services.

Levi Strauss: The Entrepreneur Who Made Gold Without Mining

One of the most famous Gold Rush entrepreneurs was Levi Strauss, a German immigrant who arrived in San Francisco in 1853. Unlike the prospectors, he had no intention of mining. Instead, he saw a massive need for durable workwear.

Strauss began by selling dry goods, fabrics, and supplies to miners, but he quickly realized miners struggled with clothing that tore too easily. Their pants ripped at the knees, pockets, and seams from carrying heavy tools and repeatedly bending throughout the day.

Strauss partnered with Jacob Davis, a Latvian-born tailor, who had developed a way to reinforce pants with copper rivets at stress points. In 1873, they received U.S. Patent No. 139,121, marking the official birth of blue jeans—pants explicitly designed to withstand the rigors of mining and hard labor.

Blue jeans quickly became a staple among workers, and their popularity spread far beyond the Gold Rush. Today, Levi’s jeans remain a global fashion icon, a $70 billion industry symbol of American ingenuity.

The Unintended Consequences of the Gold Rush

While the Gold Rush transformed California into an economic powerhouse, it also came at a devastating cost.

- Native American populations were decimated. Disease, land displacement, and violent conflicts wiped out entire tribes.

- Environmental destruction was widespread. Mining operations polluted rivers with mercury and sediment, permanently altering landscapes.

- Inflation made life nearly impossible for non-miners. As demand surged, prices skyrocketed, challenging basic survival for those who didn’t strike gold.

Despite these challenges, the Gold Rush forever changed California, laying the foundation for its future economic and cultural dominance. However, decades later, the chaotic migration and public health challenges of the Gold Rush would be eerily mirrored when another rush for riches in Nome, Alaska, set the stage for one of history’s most dramatic medical rescues.

The Invention of Blue Jeans: Necessity Sparks Innovation

The Problem: Workwear That Didn’t Work

By 1853, San Francisco had transformed into a booming economic hub of the California Gold Rush. Miners, merchants, and laborers filled the city, creating a thriving yet chaotic marketplace where businesses flourished by catering to the needs of gold seekers. Among those drawn to the town was a young German immigrant named Levi Strauss, who saw a different kind of gold mine—selling durable clothing and supplies to miners rather than mining for gold himself.

At the time, most miners wore wool trousers, canvas work pants, or soft cotton slacks, none well-suited for the harsh, physically demanding work of gold prospecting.

Miners faced several problems with their workwear:

- Tears and rips – Pants would rip at the knees, pockets, and seams from constant bending, lifting, and digging.

- Lack of durability – Cotton and wool wore out quickly, especially in muddy, wet, or rocky conditions.

- Discomfort – Stiff fabrics restricted movement, making it hard for miners to work for long hours.

- Expensive replacements—Clothing had to be shipped from the East Coast or Europe, making new pants costly and difficult to replace.

Miners spent long hours in muddy, unpredictable terrain, and their clothing wasn’t built to last. Some tried reinforcing their pants with patches, but this only delayed the inevitable—constant wear and tear meant miners always needed new pants.

Levi Strauss quickly recognized this gap in the market and saw an opportunity to create something better—workwear that could withstand the brutal conditions of the goldfields.

The Game-Changer: Metal Rivets and Reinforced Pants

Around this time, a Latvian-born tailor named Jacob Davis, based in Reno, Nevada had been experimenting with ways to make work pants stronger. He noticed miners and railroad workers frequently tore their pockets and seams when carrying tools, gold nuggets, or heavy equipment.

To solve this problem, Davis came up with a brilliant innovation—he reinforced the stress points of the pants with copper rivets, preventing tears in high-strain areas like pockets and seams.

Realizing that his reinforced pants could be a massive commercial success, Davis needed help patenting and mass-producing them. He contacted Levi Strauss, which had already built a strong business selling dry goods and textiles.

Strauss immediately saw the potential in Davis’s riveted pants and agreed to partner. In 1873, the two men filed for U.S. Patent No. 139,121, securing the rights to manufacture riveted denim work pants—later known as blue jeans.

The innovation was simple yet revolutionary:

- Copper rivets – Strengthened the weakest points in the pants, making them more durable than any workwear available.

- Sturdy denim fabric – Denim, a rigid yet flexible cotton fabric, was comfortable and resilient.

- Designed for laborers – Miners, railroad workers, and cowboys benefited from the reinforced, long-lasting design.

What started as a practical necessity for miners quickly became one of the most enduring fashion staples in history.

Why Blue Jeans Became an Instant Success

Once introduced, riveted denim pants became the gold standard for workers across the American West. Their popularity exploded for three key reasons:

1. Durability: Built to Last

Before Levi’s, miners went through pants in weeks or months. With reinforced rivets, jeans lasted years instead of months, saving workers money and frustration.

2. Comfort: Flexible for Hard Labor

Unlike stiff canvas or heavy wool, denim was tough but flexible, allowing greater freedom of movement for digging, climbing, and hauling heavy materials.

3. Affordability: An Investment for Workers

Though more expensive upfront, Levi’s jeans paid for themselves over time because workers didn’t have to replace them as often.

Within a few years, Levi’s denim jeans became standard attire for miners, railroad workers, cowboys, and laborers across the U.S. West. They were practical, rugged, and designed for real-world use.

By the early 20th century, blue jeans had expanded beyond just workwear—they were now a symbol of rugged individualism, rebellion, and American culture.

Beyond the Gold Rush: How Blue Jeans Became a Global Icon

At first, jeans were only worn by miners, farmers, and railroad workers, but over the next 150 years, they evolved into one of the most iconic fashion items in history.

1890s-1920s: The Rise of Workwear and Cowboys

- Cowboys and ranchers adopted jeans for their rugged durability on cattle drives.

- Levi’s added the “501” style in 1890, the first model of jeans with belt loops instead of suspenders.

- Railroad workers and lumberjacks began wearing denim for its toughness.

1930s-1950s: Hollywood and Rebellion

- Western movies turned cowboys into fashion icons, and jeans became a symbol of masculinity.

- During World War II, American soldiers wore Levi’s jeans off-duty, spreading their popularity to Europe and Asia.

- By the 1950s, blue jeans had become a symbol of youth rebellion, as worn by James Dean and Marlon Brando in movies like Rebel Without a Cause.

1960s-1980s: From Counterculture to High Fashion

- Hippies, rock stars, and civil rights activists adopted jeans as a political statement.

- Designers like Calvin Klein and Giorgio Armani began turning denim into high fashion.

- Blue jeans became a staple of everyday life, worn by construction workers, celebrities, and students alike.

Today: A $70 Billion Industry

From runways in Paris to construction sites in Texas, jeans are now a global phenomenon, generating over $70 billion in sales annually.

- They are worn by factory workers and Fortune 500 CEOs.

- They are part of school uniforms and luxury fashion collections.

- They symbolize both blue-collar resilience and high-end style.

Few items of clothing have ever achieved this level of cultural significance. Still, Levi Strauss’s original idea—to create rugged, durable pants for miners—sparked a fashion revolution that continues today.

From Workwear to Worldwide Influence

Levi Strauss arrived in San Francisco with a vision for success, but even he couldn’t have predicted that his riveted work pants would become one of the most iconic fashion items in history.

His story is a reminder that innovation often arises from necessity. This theme would repeat itself decades later in Nome, Alaska when an entirely different crisis led to another life-saving invention: the mass distribution of vaccines.

While miners profited from gold, many also fell victim to deadly diseases in overcrowded boomtowns. The same migratory patterns that spread fortune and industry also spread illness and death, which would become painfully apparent during the Nome Diphtheria Crisis of 1925.

Just as necessity led Levi Strauss to create durable workwear, another desperate situation would lead to an extraordinary act of survival—the 1925 Serum Run to Nome, Alaska.

The Deadliest Diseases of the Gold Rush Era

The California Gold Rush was a period of unprecedented migration, rapid economic growth, and urban expansion, but it also unleashed a wave of public health disasters. With hundreds of thousands of people crammed into hastily built towns, lacking clean water, proper sanitation, or medical care, disease spread like wildfire.

While some prospectors struck it rich, others fell victim to deadly epidemics. The same conditions that fueled economic expansion also created the perfect storm for infectious diseases to thrive.

Among the most feared illnesses of the Gold Rush era were:

- Cholera – a waterborne disease that could kill within hours.

- Typhoid fever – a bacterial infection spread through contaminated food and water.

- Tuberculosis (TB) – is an airborne disease that thrives in overcrowded and poorly ventilated settlements.

These diseases didn’t just affect miners—they spread to everyone in the boomtowns, from laborers and business owners to women and children. The lack of public health measures, sanitation systems, and medical knowledge turned California’s Gold Rush towns into breeding grounds for epidemics.

Cholera: The Waterborne Killer That Swept the Goldfields

One of the most feared diseases of the 19th century was cholera, a bacterial infection caused by Vibrio cholerae. It spread through contaminated water and food, making it particularly deadly in overcrowded, unsanitary boomtowns.

How Cholera Spread in Gold Rush Towns

Most mining camps and towns had no sewage systems or running water. Waste from thousands of people flowed directly into nearby rivers, lakes, and wells, contaminating drinking water.

- Miners unknowingly drank infected water, consuming the bacteria.

- Vendors sold tainted food, often prepared without proper hygiene.

- Lack of proper waste disposal allowed human and animal feces to mix with drinking sources.

The result? Cholera outbreaks could wipe out entire mining camps in days.

Symptoms of Cholera: Death by Dehydration

Once a person contracted cholera, symptoms could appear within hours.

- Severe diarrhea and vomiting – The body lost fluids at an alarming rate.

- Dehydration and muscle cramps – Patients became weak, dizzy, and unable to stand.

- Sunken eyes and bluish skin – A sign of extreme fluid loss and impending death.

Without treatment, death could occur in less than 24 hours. Many victims collapsed in the streets, unable to seek help. Entire towns were emptied overnight as panicked survivors fled to avoid infection.

The 1855 Cholera Epidemic: A Public Health Catastrophe

By 1855, cholera had become an uncontrollable crisis in California. The largest outbreak occurred in Sacramento, rapidly growing into a significant Gold Rush hub.

Why Sacramento Was the Epicenter

- The city’s population had exploded too quickly, leading to severe overcrowding.

- Waste and garbage were dumped directly into the Sacramento River, the primary source of drinking water.

- Medical knowledge was primitive, and doctors didn’t understand that contaminated water was the cause.

The outbreak spread like wildfire, killing thousands within weeks. Panic gripped the city, and many fled to the hills, abandoning their homes and businesses.

San Francisco also suffered heavily—with no knowledge of germ theory, people blamed bad air, immoral behavior, and divine punishment instead of contaminated water.

It wasn’t until the late 19th century that scientists like John Snow in London and Robert Koch in Germany proved that bacteria caused cholera—but by then, tens of thousands had already died from preventable outbreaks.

Typhoid Fever: The Hidden Threat in Food and Water

While cholera was an explosive killer, typhoid fever was a slow-burning epidemic that plagued Gold Rush towns for years.

What Is Typhoid Fever?

Typhoid fever is caused by the bacterium Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi. It spreads through contaminated food and water, especially where human waste is mixed with drinking supplies.

How It Infected Gold Rush Towns

- Miners drank from the same rivers and lakes where human and animal waste was dumped.

- Food vendors prepared meals with unclean hands, spreading bacteria to customers.

- Outhouses overflowed, contaminating groundwater.

Once infected, a person could unknowingly spread typhoid for weeks, leading to slow, persistent outbreaks.

Symptoms of Typhoid: The Lingering Killer

Unlike cholera, which killed quickly, typhoid fever was a drawn-out illness that could last weeks or months.

- High fever and weakness – Patients were bedridden for long periods.

- Severe abdominal pain – The infection attacks the intestines, sometimes causing perforation.

- Rashes and skin discoloration – A telltale sign of severe infection.

Even those who survived typhoid were often left permanently weakened—a dangerous reality for miners, who relied on their strength to survive.

Tuberculosis: The Silent Epidemic That Thrived in Boomtowns

Another deadly disease that thrived in Gold Rush towns was tuberculosis (TB), also known as “consumption” due to the way it gradually wasted away its victims.

How Tuberculosis Spread

Unlike cholera or typhoid, which were spread through water, tuberculosis was airborne. This made it especially dangerous in crowded mining camps where men slept in close quarters.

- Cramped housing and poor ventilation allowed TB to spread quickly.

- Shared tools, bedding, and drinking cups transferred bacteria between miners.

- Malnutrition and exhaustion weaken immune systems, making infection more likely to turn deadly.

Symptoms of Tuberculosis

TB was a slow-moving killer, often taking years to claim its victims.

- Chronic cough, often with bloody mucus – The lungs deteriorated over time.

- Extreme weight loss and fatigue – Patients wasted away, leading to the name “consumption.”

- Fever and night sweats – The infection gradually drained the body.

Since there were no antibiotics, tuberculosis was often a death sentence. Many infected miners left their camps to return home and die, spreading the disease further.

A Deadly Pattern Repeated: The Nome Diphtheria Epidemic of 1925

The same patterns of disease and migration seen during the Gold Rush would repeat themselves decades later in Nome, Alaska.

- Just as mining towns struggled with cholera, typhoid, and tuberculosis, Nome faced a diphtheria outbreak that threatened to wipe out its entire population.

- Like California boomtowns, Nome had poor sanitation, overcrowding, and a rapidly growing population, creating the perfect conditions for an epidemic.

- When diphtheria struck Nome’s children, the town’s only doctor, Dr. Curtis Welch, realized that without antitoxin, the entire community could perish.

- With ships frozen in the harbor and planes unable to fly, Nome was cut off from medical supplies—just as many Gold Rush towns had been during cholera outbreaks.

What followed in 1925 was one of the greatest medical rescues in history: the Nome Serum Run, in which mushers and sled dogs braved the Arctic winter to save an entire town from diphtheria.

Diphtheria: The Silent Killer That Struck Nome

While the California Gold Rush had its deadly outbreaks of cholera, typhoid, and tuberculosis, another highly contagious and often fatal disease would strike decades later in a remote town in Alaska.

In 1925, Nome, Alaska, found itself at the center of a diphtheria epidemic that threatened to wipe out its entire population—especially its children. With no roads, frozen waterways, and no way to airlift medicine, Nome was utterly cut off from the world, and without treatment, the town faced certain catastrophes.

To understand why the 1925 Nome Diphtheria Crisis was so devastating, it’s essential to examine diphtheria, its spread, and why it was one of the most feared diseases of the early 20th century.

What Is Diphtheria?

Diphtheria is a highly contagious bacterial infection caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Unlike many other bacterial infections, which primarily affect the lungs or digestive system, diphtheria attacks multiple organ systems, making it especially lethal.

The real danger comes from the diphtheria toxin, which destroys healthy tissues, leading to:

- Severe respiratory distress

- Heart failure

- Paralysis

- Death

Before the development of a vaccine and antitoxin, diphtheria was known as the “strangling angel of children” because of its high mortality rate among young patients.

How Diphtheria Spreads

Diphtheria is an airborne disease that spreads rapidly in crowded conditions, much like tuberculosis.

Modes of Transmission

- Respiratory droplets – When an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks, they release bacteria into the air, allowing others to inhale it.

- Contaminated surfaces – Diphtheria bacteria can survive on objects like clothing, toys, bedding, and doorknobs, infecting those who touch them for weeks.

- Close contact – Schools, homes, and overcrowded environments were hotspots for diphtheria outbreaks, making it a constant threat to children.

Nome, Alaska, with its close-knit population, harsh Arctic climate, and poor ventilation indoors, was the perfect breeding ground for a deadly outbreak.

Symptoms of Diphtheria: The Deadly Progression

Unlike many illnesses that gradually worsen over time, diphtheria can become life-threatening in just a few days.

Stage 1: Early Symptoms (Days 1-5)

Diphtheria often begins like a mild cold, which tricks people into underestimating its danger.

- Sore throat and hoarseness

- Mild fever (101°F or lower)

- Fatigue and muscle weakness

- Swollen lymph nodes in the neck

At this stage, many misdiagnose diphtheria as strep throat or the flu, delaying critical treatment.

Stage 2: The Formation of the Pseudomembrane

As the bacteria multiply, they release a toxin that destroys healthy tissue in the throat.

- This dead tissue builds into a thick, grayish-white layer called a pseudomembrane.

- The pseudomembrane coats the throat and airways, making breathing increasingly difficult.

- If a doctor tries to remove it, it bleeds heavily, often worsening the patient’s condition.

Many victims of diphtheria died simply because they suffocated—the growing membrane completely blocked their airways.

Stage 3: Systemic Toxin Effects

Even if a patient survives the initial respiratory distress, the diphtheria toxin spreads through the bloodstream, attacking vital organs.

- Paralysis – The toxin damages nerves, causing muscle paralysis in the arms, legs, and diaphragm.

- Heart failure – The toxin weakens heart muscles, leading to fatal arrhythmias or heart attacks.

- Kidney and liver damage – The toxin poisons internal organs, leading to multi-organ failure.

Without antitoxin treatment, up to 50% of infected children died.

Why Nome Was at High Risk for an Outbreak

By the time diphtheria reached Nome in 1925, the town was already disadvantaged by public health. Nome had all the risk factors for a deadly outbreak, making it impossible to contain the disease without medical intervention.

1. Nome’s Isolation and Harsh Climate

Nome was wholly cut off from the outside world for six months of the year due to Arctic ice.

- No roads connected Nome to significant cities.

- The Bering Sea was frozen solid, making ship travel impossible.

- Air travel was new, and planes couldn’t fly in severe winter blizzards.

Once diphtheria reached Nome, there was no conventional way to get help or medicine.

2. Lack of Medical Resources

Nome had only one doctor, Dr. Curtis Welch, and a small hospital with limited supplies.

- The town’s last batch of diphtheria antitoxin had expired, making it too risky to use.

- There were no backup medical facilities. The closest source of fresh antitoxin was Anchorage, 674 miles away.

- The town had no trained specialists—Dr. Welch was handling the outbreak alone, with only a handful of nurses.

3. Overcrowded and Vulnerable Population

Nome had a growing population of around 1,400 people, including many children who had never been vaccinated.

- Many residents lived in close quarters, increasing exposure to the disease.

- The harsh winter forced everyone indoors, where poor ventilation helped spread infection faster.

- Alaska Natives were particularly at risk—they had limited immunity to European-introduced diseases, making them more likely to suffer severe complications.

By January 1925, diphtheria had begun claiming lives, and Dr. Welch knew the entire town could be wiped out if he didn’t act fast.

The Urgency of the 1925 Nome Diphtheria Crisis

Without a fresh supply of diphtheria antitoxin, every infected child in Nome was facing certain death.

Dr. Welch sent an urgent telegram to Anchorage, pleading for emergency medical aid.

The challenge? Getting 20 pounds of life-saving serum to Nome—674 miles away—in the middle of an Arctic winter.

- Ships couldn’t reach Nome – The harbor was frozen solid.

- Planes were unreliable – Blizzards, subzero temperatures, and primitive aircraft made flying nearly impossible.

- There were no roads – hundreds of miles of frozen wilderness surrounded Nome.

With all modern transportation ruled out, officials turned to Alaska’s oldest and most reliable form of transport—sled dog teams.

What followed was one of the greatest medical rescues in history: a 674-mile sled dog relay across treacherous Arctic terrain. Mushers and their dogs battled hurricane-force winds, frostbite, and exhaustion to save the town of Nome.

The 1925 Nome Serum Run: A Race Against Death

In the dead of winter, amidst the harsh Arctic landscape of Alaska, the town of Nome faced a crisis that threatened to wipe out its entire population. A diphtheria outbreak had begun, and without access to life-saving antitoxin, the children of Nome were at imminent risk of death.

At a time when modern transportation was still in its infancy, Nome was entirely cut off from the rest of the world for months at a time. Ships couldn’t reach the icebound harbor, and early airplanes were unreliable in extreme weather conditions. The town’s only doctor, Dr. Curtis Welch, realized that if they didn’t get a fresh supply of diphtheria antitoxin soon, hundreds of people—mostly children—would die in a matter of weeks.

The only hope was an unprecedented, high-risk sled dog relay that would require braving hurricane-force blizzards, subzero temperatures, and dangerous ice crossings. This desperate mission, now known as The Great Race of Mercy, would be one of the most extraordinary feats of endurance and medical rescues ever recorded.

Nome’s Crisis: A Town on the Brink of Disaster

By January 1925, diphtheria had already begun spreading among Nome’s children. The town’s only supply of antitoxin had expired, and Dr. Welch feared using it would be as dangerous as the disease itself.

At the time, Nome was home to approximately 1,400 residents, many of whom were Alaska Natives with little immunity to European diseases. The harsh Arctic winter forced families to stay indoors, creating the perfect conditions for spreading the disease.

Nome was utterly isolated, with no roads or railways and no way to receive emergency medical supplies. The nearest batch of fresh diphtheria antitoxin was in Anchorage, more than 1,000 miles away. Getting the medicine to Nome in time was an insurmountable challenge.

Dr. Welch knew that the outbreak could wipe out entire families if he didn’t act immediately. He sent a desperate telegram to Anchorage, pleading for help. However, with modern transportation ultimately ruled out, officials were left with one final option—an emergency sled dog relay across 674 miles of frozen wilderness.

The Plan: A 674-Mile Dog Sled Relay Through Arctic Conditions

To accomplish what seemed like an impossible mission, the best mushers and sled dog teams in Alaska were recruited to form a relay system. At checkpoints along the route, they passed off the 20-pound package of diphtheria antitoxin like a baton.

The journey would begin in Nenana, where the serum had been transported by train from Anchorage. From there, a series of sled dog teams would race against time, battling subzero temperatures, howling winds, and dangerous terrain to reach Nome.

The route was treacherous:

- 20 mushers and 150 sled dogs would take part in the mission.

- The teams would cover 674 miles in less than six days, averaging fast speeds over unpredictable terrain.

- Temperatures would drop to -60°F (-51°C), with hurricane-force winds capable of blowing sleds off course.

- The antitoxin itself was fragile—if it froze, it would become useless, and if it was shaken too much, it could lose its potency.

Despite the extraordinary risk, the mushers knew that every moment counted. They set out into the storm, knowing that the lives of countless children depended on their endurance, skill, and the loyalty of their sled dogs.

A Life-Threatening Journey Across the Frozen North

The Serum Run was not just a race but a battle against nature’s most unforgiving forces.

Mushers and their dogs faced some of the worst Arctic conditions imaginable. Temperatures plummeted well below -50°F, with winds reaching 80 miles per hour, creating whiteout blizzards that reduced visibility to nearly zero.

The path was riddled with dangers:

- Treacherous ice crossings – Some teams had to traverse frozen rivers and lakes, where one misstep could send them plunging into freezing waters.

- Blinding snowstorms—Visibility was so poor that mushers often had to trust their lead dogs to find their way forward.

- Fatigue and frostbite – The teams raced day and night with little rest, and many mushers suffered from frostbite, exhaustion, and hypothermia.

Yet, despite these brutal conditions, the mushers and their dogs never turned back. They pushed forward, knowing that failure was not an option.

Togo vs. Balto: Who Was the True Hero?

While Balto is widely remembered as the hero of the Serum Run, the reality is more complex. Another sled dog, Togo, played a far more grueling and demanding role in the mission.

Togo: The Unsung Champion

- He led his team through the most extended and dangerous leg of the journey—covering 260 miles in -60°F temperatures.

- They braved the treacherous crossing of Norton Sound, a frozen stretch of ocean that could crack and collapse beneath them at any moment.

- Ran over 12 hours straight without rest, covering 84 miles in a single night, an unprecedented endurance feat in sled dog racing history.

Togo’s musher, Leonhard Seppala, was one of Alaska’s most skilled and experienced dog sled racers. Initially, he underestimated Togo’s potential, believing him too small and unruly to be a lead sled dog. But over time, Togo proved his unmatched intelligence and endurance, ultimately becoming one of the greatest sled dogs in history.

Many historians argue that the serum would have never made it to Nome in time without Togo.

Balto: The Finishing Touch

- While Togo ran the longest and most challenging stretch, Balto led the final 55-mile leg to Nome.

- Balto’s musher, Gunnar Kaasen, arrived in Nome with the serum, meaning Balto was the first dog reporters and photographers saw upon arrival.

- Balto received most of the public credit despite Togo’s far more significant contribution to the mission.

Togo and Balto played essential roles in saving Nome and the other mushers and sled dogs who risked their lives to ensure the antitoxin reached the town before it was too late.

A Legendary Medical Rescue

After six days of nonstop travel, the diphtheria antitoxin finally arrived in Nome on February 2, 1925.

- Within hours of receiving the serum, Dr. Welch and his team began administering life-saving doses to infected patients.

- The outbreak was contained, preventing the mass death toll that Dr. Welch had feared.

- Nome survived one of the worst public health crises in Arctic history thanks to the bravery of the mushers and sled dogs.

The Serum Run became a global sensation, with newspapers around the world reporting on the incredible efforts of the sled dog teams. The event remains one of the most famous examples of teamwork, endurance, and heroism in medical history.

The Lasting Legacy of the Nome Serum Run

The 1925 Nome Serum Run was not just a remarkable feat of endurance and heroism—it had a profound and lasting impact on public health, vaccine awareness, and the role of sled dogs in history. What began as a desperate race against time to save a remote town ultimately changed how the world viewed vaccination programs, emergency medicine, and animal-assisted transport.

Nearly a century later, the lessons of the Serum Run still resonate, reminding us of both the power of human determination and the critical importance of disease prevention.

The Expansion of Vaccination Programs

One of the most significant outcomes of the Serum Run was the widespread recognition of the importance of vaccines.

At the time, diphtheria was a major public health threat, particularly in isolated communities with limited access to medical care. While antitoxin treatment was available, it was only effective after infection. The only real way to prevent future outbreaks was through mass vaccination programs.

How the Serum Run Changed Vaccine Policy

- Increased public awareness – The global media coverage of the Nome crisis highlighted the dangers of diphtheria, leading to greater demand for vaccinations.

- Expanded immunization efforts – Public health officials pushed for widespread diphtheria vaccinations, especially in rural and underserved areas.

- By the 1940s and 1950s, diphtheria vaccination became routine, and cases began to plummet worldwide.

- Today, diphtheria is largely eradicated in many countries, thanks to the DTP vaccine (diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis), part of routine childhood immunization schedules.

Without the Nome Serum Run and the heightened awareness it generated, it’s possible that vaccination efforts would have been slower to develop, leading to more preventable deaths in the following decades.

The Nome Serum Run and the Birth of the Iditarod

Another lasting impact of the Serum Run was its role in inspiring the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, one of the most famous endurance races in the world.

Before the advent of snowmobiles and airplanes, sled dogs were the primary method of transportation in Alaska, used for everything from mail delivery to freight hauling. The Serum Run was the final historic demonstration of sled dogs’ vital role in survival before modern technology took over.

The Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race was founded in 1973 to commemorate the heroic efforts of mushers and their sled dogs.

How the Iditarod Honors the Serum Run

- The race follows part of the historic Serum Run route, retracing the path taken by the mushers in 1925.

- It is a living tribute to sled dog culture and the remarkable endurance of humans and animals.

- The Iditarod keeps the legacy of Togo, Balto, and the other sled dogs alive, ensuring their contributions are never forgotten.

Today, the Iditarod is one of the most grueling endurance races in the world. It covers approximately 1,000 miles of frozen terrain, keeping alive the Alaskan sled dog tradition that once saved an entire town.

Togo and Balto: Ensuring Their Place in History

While Togo and Balto played critical roles in the Serum Run, their legacies took very different paths.

Togo: The Overlooked Champion Finally Recognized

For decades after the Serum Run, Balto overshadowed Togo’s contributions. While Balto received statues, movie adaptations, and international fame, Togo remained largely forgotten outside Alaska.

However, as historians reexamined the records, it became clear that Togo had run the most extended and most dangerous leg of the relay, covering 260 miles compared to Balto’s 55 miles.

Today, Togo’s legacy has been rightfully restored:

- In 2019, Disney released the movie “Togo,” starring Willem Dafoe, finally giving the dog his due recognition.

- The Togo statue at the Iditarod Headquarters in Alaska ensures his name is forever associated with the Serum Run.

- Many now regard Togo—not Balto—as the true hero of the mission.

Balto: A Symbol of Sled Dog Heroism

Although Balto’s stretch was shorter, his role in leading the final leg of the journey made him the most visible sled dog of the Serum Run.

- In 1925, a statue of Balto was erected in New York City’s Central Park, honoring him as a symbol of heroism and endurance.

- Balto’s fame sparked greater awareness of the importance of working sled dogs, and he spent the rest of his life as a celebrated figure.

- His preserved body is on display at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, where thousands visit to pay tribute to the dog who helped save Nome.

While Togo deserved more recognition, Balto’s impact as a public icon helped ensure that the Serum Run was never forgotten.

The Nome Serum Run helped elevate the status of working dogs in medicine and emergency response. Even today, dogs play a vital role in search-and-rescue missions, medical alert services, and therapy programs.

Conclusion: A Testament to Bravery and Survival

The 1925 Nome Serum Run was more than just a race to deliver medicine—it was a testament to human determination, teamwork, and the extraordinary capabilities of sled dogs.

It helped push forward mass vaccination programs, solidified the role of working dogs in history, and inspired the creation of the Iditarod, ensuring that the heroism of the mushers and their dogs would never be forgotten.

Nearly 100 years later, the Serum Run remains a symbol of courage, endurance, and the power of a community coming together in a crisis.

It is a story of survival against impossible odds, proving that sometimes, heroes don’t wear capes—they wear harnesses and pull sleds through the snow.

Full Transcript and Acknowledgments for Episode 10: Antitoxin Togo, Please

In this episode, we explore the surprising connections between the California Gold Rush, Levi Strauss’ iconic blue jeans, and the 1925 Serum Run to Nome—a race against time to stop a deadly diphtheria outbreak.

How did denim shape American history? How did sled dogs become medical heroes? Read the full conversation between Dr. Dustin Edwards and Faith Cox below to uncover the fascinating intersections of history, microbiology, and innovation.

Show Notes

(0:00 – 0:04)

Let’s play a game. Things that are timeless. Go.

(0:04 – 0:07)

Um, red lipstick. Blue jeans. Henleys.

(0:09 – 0:14)

Um… Let’s play a game. Things that are not timeless. Um, micro-bangs.

(0:15 – 0:18)

Molots. Low-rise jeans. Crocs.

(0:20 – 0:28)

Um, wearing skirts over jeans. And… dresses over jeans. Um, also, diphtheria is not timeless.

(0:29 – 0:37)

I’m Dr. Dustin Edwards. And I’m Faith Cox. Welcome to Germomics, where we go to B from A in the most roundabout way and make microbiology and history.

(0:38 – 0:53)

This series connects different aspects of modern life and society to mind groups receiving unconnected natural events, discoveries, and inventions. So, how does timeless fashion connect to diphtheria? Let’s find out. There is evidence of pants made of denim from Nimes, France.

(0:53 – 1:02)

Thus, denim. This fabric was made into jeans in Genoa around 1800. And they dyed these jeans blue.

(1:02 – 1:13)

And thus, they were named Bleu de Jeans. But when thinking about blue jeans, we often think of Levi Strauss. Levi Strauss was an immigrant, aged 18 and poor when he arrived in the U.S. with his mother and brothers.

(1:13 – 1:27)

He helped his family by working in their dry goods store in New York. He eventually opened his store in San Francisco in 1853 at 25. He sold clothing, bedding, combs, purses, handkerchiefs, and even tents at this store.

(1:28 – 1:48)

In 1871, a tailor named Jacob Davis in Reno, Nevada, was approached by a miner’s wife, asking him to make a pair of pants that could take some abuse. Inspired by the different harnesses and fasteners around him, he tried to add rivets to the weak spots on jeans, such as at the pockets or the fly. And it worked.

(1:48 – 1:56)

The riveted pants were much more durable. And he knew he was onto something big. The problem was that Davis didn’t have enough money to file a patent.

(1:56 – 2:12)

He didn’t even know how to go through the whole process. So he turned to the person he was buying the fabric from, Levi Strauss. The two struck a deal, and Davis moved to San Francisco to oversee production of this new product while Strauss managed the business side.

(2:13 – 2:32)

The patent expired in 1890. Yet 130 years later, one brand is synonymous with blue jeans and their association with the global cultural success of the American century. Levi Strauss moved to San Francisco to compete in the enormous sales opportunity generated by the California Gold Rush that started in 1848 or 1849.

(2:33 – 2:54)

Six years before Strauss moved to San Francisco, the town’s population boomed from 200 people to over 36,000. But still, the city only had a population of 36,000, and it already had around 120 dry goods stores. However, Strauss succeeded in this crowded space because he kept his stores stocked with supplies from his family businesses from back east.

(2:54 – 3:24)

The California Gold Rush began just after the end of the Mexican-American War, and at that time, California was sparsely populated. There were about 6,500 Spanish-Mexican Californios, 700 foreigners, including Americans, and 150,000 Native Americans. Of those Native Americans, 120,000, or about 90%, would die from disease, starvation, or attacks and murder over just a few years.

(3:25 – 3:53)

However, the discovery of gold by James Marshall at a sawmill owned by John Sutter in Central California ushered in a mass migration of people worldwide, with over 300,000 people moving there in search of riches. Early prospectors averaged daily gold finds worth 10 times the average wage of a laborer on the East Coast. What’s interesting about gold in California is that it was heavily concentrated in gravel creek beds, so you could quickly grab flakes or nuggets with just your hands.

(3:54 – 4:11)

Individuals could also pan for gold using simple bowls and plates. Altogether, 750,000 pounds of gold were extracted during the California Gold Rush, worth tens of billions of today’s dollars. The impact of the value of the gold and the population influx hurried California to statehood in just 1850.

(4:11 – 4:48)

And that’s just crazy. So, about four years earlier, a small group of only 33 American insurgents entered California without permission and started what was later known as the Bear Flag Revolt to form the Republic of California, which was an unrecognized breakaway state for about 25 days. This was followed by the two years of the Mexican-American War, of which disagreements on the borders of Texas are partially to blame for causing that conflict. Then, these people just showed up for the gold and created this major population center.

(4:49 – 5:22)

The Compromise of 1850 was a series of five bills passed by Congress to defuse the growing political confrontation of slavery that would eventually lead to the Civil War. It included making California a free state as a balance to Texas, a slave state. This compromise also set Texas’s borders for what they are today. Forty years after the California Gold Rush, in 1896, gold is found in Canada by the Alaskan border, starting the Klondike Gold Rush, started by George Carmack and Skookum Jim Mason.

(5:22 – 5:39)

Eventually, over $1 billion in gold would be extracted from Klondike. Similar to California, a mass migration of 100,000 people happened, including Jack London, who wrote The Call of the Wild. However, unlike California, the paths in Alaska and Western Canada are even more remote and inhospitable.

(5:40 – 5:51)

The Chilkoot Trail and the White Pass Trail were the most prominent routes. Chilkoot Trail was very steep. I saw a photo of it, which looked like a ski lift at a resort.

(5:51 – 6:10)

So, it was extraordinarily steep and covered in snow. It was too steep for pack animals, so people had to try to move it themselves in stages up the mountain and across the pass. The White Pass Trail, on the other hand, was a newer route to the Klondike.

(6:10 – 6:33)

It was not nearly as steep. However, it was just covered in mud, making it almost impossible to get through it during the fall months. Conditions and travel were so rough that the Canadian police would not allow people to enter the trails unless they had over one year’s worth of supplies, which ended up weighing nearly a ton, 2,000 pounds.

(6:33 – 7:13)

Of the approximately 100,000 people who entered the Klondike, only about 4,000 people found gold. The Klondike gold rush ended quickly for various reasons, including the fact that gold was seen elsewhere, which was much easier to get to, including in Nome, Alaska. Nome was a lot easier to get to then.

The Klondike and the gold were just lying on the beach. You didn’t even need to stake a claim to the land. Between 1900 and 1909, the town reached a population of 20,000, with many of those coming from the Klondike, including Wyatt Earp, who was earlier made famous at the gunfight at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona.

(7:13 – 7:43)

I was forced to watch the movie Tombstone by my count several hundred times. What do you mean forced? And by whom? So I had a roommate who enjoyed country-western dancing, and he would go out fairly often, two or three times a week. And sometimes he would bring back a friend he had met, put on Tombstone, and then leave towards his bedroom to get cleaned up or whatever.

(7:44 – 8:01)

And so I would have to sit there and entertain their friend while watching the movie Tombstone. And then my friend would eventually come back and start, like, quoting Tombstone, I’ll be your huckleberry, and then would leave. And so I have that movie wholly memorized.

(8:01 – 8:09)

Oh, I’m sorry. It’s a good movie full of one-liners. So, at Nome, tent cities covered the shoreline.

(8:10 – 8:42)

I saw pictures, again, of the Nome Gold Rush, and it is, as far as I can see, these white tents all along the water. By 1910, though, there were only about 2,600 people left. However, Nome survives today as a permanent settlement and currently has a population of about 3,800 people, which is remarkable because it is pretty distant. It’s near the Arctic Circle, and it has very long, freezing, very dark winters and very short and cool summers.

(8:42 – 8:57)

Fifteen years after the Gold Rush, in 1925, from November until July, the port at Nome had iced over. The town had one doctor, Curtis Welch, and four nurses. After the last ship had sailed in December, the doctor treated several small children for sore throats and tonsillitis.

(8:58 – 9:18)

Over the next few weeks, several other children had similar symptoms, and four died. By January, he began to observe a white pseudomembrane at the back of the throat of some children, a classic symptom of diphtheria. Unfortunately, all the diphtheria antitoxin he had in his office had expired, and while he had ordered more antitoxin several months before, none had arrived before the port closed.

(9:19 – 9:33)

I want to note that the antitoxin we’re discussing differs from the vaccine administered today, so this was just a treatment for diphtheria. It was not preventative. Antibodies were derived from inoculating a horse and then using the horse serum.

(9:33 – 9:48)

Yes, yes, the horse’s antibodies then neutralize the pathogen. Realizing an epidemic could occur, the physician and town leaders held a meeting, and they enacted a quarantine. See, just six years earlier, the Spanish flu had killed 50% of the Alaskan native population there.

(9:48 – 10:04)

The town feared that the diphtheria epidemic would have a near 100% mortality rate in that area. Dr. Welch sent a telegram stating that an outbreak of diphtheria was almost inevitable here.

Stop. I am in urgent need of one million units of diphtheria antitoxin. Stop.

(10:05 – 10:18)

Mail is the only form of transportation. Stop. I have already applied to the Commissioner of Health of the territories for antitoxin.

Stop. There are about 3,000 white natives in the district. There were three planes in Alaska in 1925.

(10:19 – 10:43)

However, they were unsuitable for winter use and were dismantled at the time. In addition, all experienced pilots were down in the contiguous U.S. The town decided to try using sled dog teams across Alaska, 674 miles across Alaska in winter. Further, Dr. Welch calculated that the antitoxin would be viable for only about six days in such harsh conditions.

(10:43 – 11:01)

So that means that they would have to make their way all across this enormous territory in just five and a half days. The plan would be to start in Nome and the other in Nenana near Fairbanks in the eastern part of the territory. And we would need to meet in the middle in New Lotto.

(11:02 – 11:14)

The trip from New Lotto to Nome usually takes about 30 days. However, one record was set at nine days. This is much longer than five or six days.

(11:14 – 11:26)

They were trying to make it in just a little over half of what was the record. Yes, in what was usually 30 days. In winter? In winter. In Alaska? In Alaska.

(11:28 – 11:48)

After the telegram was received, over a million antitoxin units were found along the West Coast and sent to Seattle, where they were then shipped to Seward, Alaska. However, all of the antitoxins would take some time to arrive. However, 300,000 units were found in Anchorage and sent to Nenana.

(11:48 – 12:12)

While not enough to stop the epidemic, it was enough to treat 15 patients and could slow down the spread of diphtheria until the larger shipment arrived. In the meantime, despite being less effective, Dr. Welch would use the rest of his expired antitoxin. The governor gave final approval, and on January 27th, the first dogsled relay began.

(12:12 – 12:32)

The region was experiencing 20-year lows with temperatures at about negative 50 to negative 62 Fahrenheit, which is insane. I’ve never even experienced like negatives. In addition, there were blizzard whiteout conditions with gale-force and hurricane-force winds.

(12:32 – 12:54)

And because it was winter near the Arctic Circle, there were only about five hours of sunlight due to polar night. During the first leg of the relay, within hours, parts of the face of the first musher had already turned black from hypothermia. At the first checkpoint of Minto, from his team of 11 dogs, three were beginning to struggle and had to be left behind.

(12:55 – 13:16)

By January 30th, the number of diphtheria cases reached 27, and yet another child had died. On New Year’s Eve, on January 31st, Leonard Sapala and his lead dog, Togo, brought the antiserum the most hazardous and furthest distance, covering twice the distance of any other team. And he did it during a storm.

(13:17 – 13:42)

So, Sapala had an eight-year-old daughter who was at risk of developing diphtheria, so he had an obvious stake in the game. But the town elected him to do this, the most extended and most hazardous portion, because he was considered to be the most experienced of all of the sled dog drivers. So there was even this portion where it wasn’t a route recommended to be taken on a normal day under normal conditions, even on a good day, good conditions.

(13:43 – 14:02)

It was this last resort route that, when taken, can shave a whole day off travel. And he had taken it several times, but to do it, you have to cross this body of water. In the body of water, it is frozen over, the wind weathers it, and it develops cracks that make it easy for the dogs to land their claws in and then break the ice.

(14:02 – 14:20)

And so if you do that too often and your dogs aren’t over it, you can fall through. But he was elected to cover this not just one way but both ways to get the antitoxin there and back, and he did it successfully. But apparently, there was an eyewitness account shortly after he did it, just a couple of hours after he had finished crossing it.

(14:20 – 14:31)

The dogs had tripled the ice so much that it was broken. You couldn’t cross the river anymore. On February 2nd, on the final leg of the journey, Gunnar Kasson and his lead dog Balto arrived in Nome.

(14:32 – 14:59)

Altogether, the trip took 127 hours, 20 teams with over 150 dogs, and several of these dogs perished. However, the antitoxin was adequate, the epidemic ended, and there were only about 5 to 7 deaths recorded. However, it is unknown how many native lives were lost, but it is estimated to be over 100.

(15:00 – 15:24)

Today, there is a statue of Balto in Central Park, a movie called Balto, and an upcoming film about Togo. The Great Race of Mercy, as it was later called, is now commemorated each year by the Iditarod Trail Sled Race. The causative agent of diphtheria is Carinibacterium diphtheriae, also known as Klebs Loffler bacillus, after the scientist who discovered it.

(15:25 – 15:46)

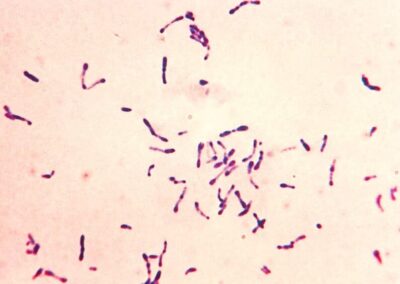

It was discovered in 1884 by German bacteriologists Edward Klebs and Friedrich Loffler. Corynebacterium diphtheriae is a gram-positive pleomorphic bacillus, so gram-positive meaning it has simply a cell wall and an inner membrane. Pleomorphic describes the ability of the bacteria to change its shape based on its environment.

(15:47 – 16:07)

Three main subspecies differ slightly in their colonial morphology and biochemical properties, such as their ability to metabolize different nutrients. All three subspecies can be toxigenic and cause diphtheria. The toxigenicity is determined by whether a bacterial genome has a specific bacteriophage encoded.

(16:07 – 16:25)

They’re called prophages when a bacteriophage is integrated into a bacterial genome. The phage genome contains the toxin gene, and the bacteria can express the toxin. In other words, if a bacterium does not integrate the prophage into the genome, it is considered a non-toxigenic strain.

(16:25 – 16:48)

If it has the prophage with the toxin gene integrated into the genome, it’s considered a toxigenic strain. Corynebacterium diphtheriae can also cause a cutaneous infection involving the skin, eyes, or genitals, but we will focus on respiratory diphtheria. So, the symptoms can be mild to severe, usually between two to five days after exposure, beginning with a sore throat and a fever.

(16:48 – 17:19)

After that, the lymph nodes may begin to swell, and in severe cases, patients may develop a gray or white patch in the back of the throat called a pseudomembrane. The pseudomembrane can form in the mucous membranes where the bacteria colonizes, in the nasal tract, or the throat. Still, I will focus on the pseudomembrane’s development in the throat. So there, the pseudomembrane begins in small patches, but it can grow in size, eventually covering the entire back of the throat in a large patch and then developing into a gray-black or green color.

(17:19 – 17:42)

The disease mainly spreads through aerosolized respiratory droplets from coughing or sneezing, and the main virulence factor in diphtheria is diphtheria toxin. The toxin inactivates eukaryotic elongation factor 2, essential for protein synthesis. Cells must produce proteins to survive, so when this protein is inactivated, it will eventually cause cell death.

(17:43 – 18:18)

After the cells die, immune cells then go to deal with all these dead cells in the throat, as well as colonizing bacteria, and eventually, a coagulum of fibrin, white blood cells, and cellular debris due to cell death all form into the pseudomembrane. As the disease progresses, the pseudomembrane can change from white or gray to having patches of green or black due to necrosis. Eventually, the membrane can grow so large that it affects one’s breathing ability. Combined with the lymph node swelling, the membrane and lymph nodes can produce so much that they start to obstruct the airway and eventually result in death.

(18:18 – 18:42)

Another way you can die from diphtheria is that the toxin can become disseminated in the blood and cause damage to other organs, so this can be particularly damaging to the heart. The damage caused by the diphtheria toxin circulating in the blood and reaching the heart causes cell death. The heart muscle then becomes inflamed, and this inflammation can affect the heart’s electrical impulses, ultimately causing irregular heartbeats and affecting the body’s ability to pump blood.

(18:43 – 19:19)

It can also reach the nerves and cause inflammation, resulting in paralysis. It can also spread through the blood and result in necrosis of the liver and kidneys. Diphtheria is not common today.

There is currently a vaccine available for diphtheria. It’s grouped in with tetanus and pertussis, so this vaccine has different versions for different age groups. Diphtheria rates in the U.S. quickly declined after the introduction of the vaccine in the 1920s, with there being less than five reported cases of respiratory diphtheria in the last decade in the U.S. So, say someone is to come down with diphtheria, there’s also the antitoxin which can be used as treatment.

(19:19 – 19:44)

It does not technically have FDA approval, but it can be distributed to physicians by the FDA as an investigational new drug, meaning it can be given to patients with a confirmed or probable case of diphtheria. So, a confirmed case is when they have a clinical case from a toxigenic carinobacterium diphtheriae, and the bacteria is isolated. Or it is a case that can be epidemiologically linked to a laboratory-confirmed case.

(19:45 – 20:13)

Or they can have a probable case, which is when a clinically compatible case is not laboratory-confirmed. It’s not epidemiologically linked to a laboratory-confirmed case, but everything’s pointing to them having diphtheria. So, to recap, we’ve talked about Blue Jeans and Levi Strauss, Gold Rushes in California and Alaska, Togo and Balto on the Great Race of Mercy, and diphtheria. Thank you for listening to episode 11, antitoxin Togo, please.

(20:13 – 21:01)

Show notes, transcripts, citations, and social media links are available on our website at germanmix.com. So, I have three dogs, and while they are wonderful, they could never do like what the sled dogs did. So I have a blind Shih Tzu named Bosco, a deaf Shih Tzu named Bella, and then a poodle named Sugar, who isn’t always the brightest. And they don’t tolerate the rain.

Well, they almost refuse to go out in the rain and go to the bathroom. They’d instead hold it or make them go outside anyway. They do better in the snow.

They have little coats in the fall and the winter, so they tolerate snow better, except they’re all short. So my two little Shih Tzus legs, their legs are only between four to six inches long. And I remember one year a while back, we got a good amount of snow, and the snow drifts were over six inches.

(21:01 – 21:15)

And so my dog Bosco had to bunny hop around through the snow because it was too deep for him to tread through. So, there will probably not be a statue of your Shih Tzus in Central Park. No, something better.

They’re lap dogs, so they keep your toes warm.

Credits

Written and performed by Dr. Dustin Edwards and Faith Cox

Music from

In Your Arms” by Kevin MacLeod; license CC BY 4.0

Images from

Corynebacterium diphtheriae © CDC; public domain

Seppala and Togo © Carrie McLain Museum; license CC0