Confessions of a Cholera Girl

How does Steak and Eggs for breakfast help stave off cholera diarrhea cases during a disaster? Probably not how you think! In this episode, follow along as we connect the Waffle House Index, hurricanes, cholera, epidemiology, and the need for public infrastructure. Vibrio cholerae infects millions of people each year, and the cholera toxin can cause acute diarrheal disease that produces “rice water stool” and kills between 21,000 to 143,000 people worldwide annually.

Show Notes

(0:00 – 0:10)

I feel like I’m about to personally insult you, but I’ve never liked breakfast foods. What kind of breakfast foods? Like any type of breakfast foods. So I like bacon.

(0:10 – 0:17)

I particularly hate sausage. I’ve never been impressed by eggs of like any sort. But you can make all kinds of eggs.

(0:17 – 0:23)

You make scrambled eggs, scrambled eggs with cheese. You can do fried eggs. For fried eggs, you can do sunny side up.

(0:23 – 0:29)

You can do over easy. You can make omelets. Yeah, I’ve never had an omelet I was like impressed by.

(0:29 – 0:37)

There’s like whole omelet bars. I know I’ve been to like omelet bars and I’ve had them like make an omelet with what I would ideally like. And then I like cheese.

(0:37 – 0:46)

Yeah, cheese, bacon, chives, like all kinds of things that like I enjoy. But then I get the omelet and I like eat it. And I just think I would rather be eating cereal.

(0:48 – 0:55)

I’m Dr. Dustin Edwards. And I’m Faith Cox. And this is Germomics, where we go to be from A in the most roundabout way.

(0:56 – 1:10)

A mix of microbiology and history. In this series, we connect different aspects of modern life and society to microbes through seemingly unconnected natural events, discoveries, and inventions. So how do T-bone steaks link to cholera outbreaks? Let’s find out.

(1:11 – 1:33)

I hear that the Waffle House sells more T-bone steaks than anybody else in the world with like over 150 million T-bone steaks sold since they opened in 1955. Are there really that many people eating steak and eggs? I would have to guess so. I’ve never once in my life had, I guess, steak and eggs for breakfast.

(1:33 – 1:43)

I’ve always done like pancakes and bacon and eggs and toast and all the what I would call like standard things. T-bone steaks just seem too fancy for breakfast. Maybe.

(1:43 – 2:01)

OK, so my issue with breakfast foods is that I don’t think there’s like enough flavor for the amount of time you put into it. So in the time that I could make like an omelet or like scrambled eggs, I could only make spaghetti. What I’m trying to say is maybe steak and eggs would be like a better option for me because it’s like more flavor.

(2:02 – 2:07)

Maybe. Maybe. I had no idea that Waffle House was like selling that many T-bone steaks again.

(2:07 – 2:11)

Yeah. Yeah. They’re extraordinarily popular chain, I guess.

(2:11 – 2:14)

Waffle House in general or? Yes. Yes. For breakfast.

(2:15 – 2:21)

Really? Actually, probably. They’re open 24 hours a day. So you can probably eat anything you want there and probably not everything you want there.

(2:21 – 2:25)

But if you’re hungry. Yeah. Their menu is probably like 24 hours.

(2:25 – 2:28)

They’re going to be open every, yeah, around the clock. Yeah. Yeah.

(2:28 – 2:37)

Yeah. They’re open like all the time, actually, including in storms. Are you familiar with the Waffle House Index? I’ve heard of it, but I’m not overly familiar with it.

(2:38 – 3:09)

All right. What do you know about the Waffle House Index? From my understanding of it is that there are like if a storm comes through, FEMA will look to see if the Waffle House is closed or not and how many of them have closed and how long it takes for them to reopen as kind of an indicator on whether on how commerce is going to do in that area, like whether the damage from the storm was going to shut down businesses for a long time. Yeah.

(3:09 – 3:25)

That’s essentially the gist of it. So in 2004, I can’t remember his name, but the director of FEMA, he sent out his men to go drive around to see how many like Waffle Houses were open in an area. And he said, like, if they’re open and serving everything, like keep driving.

(3:25 – 3:30)

That’s not where the damage is. And if they’re like serving a limited menu, take note of it. But that’s not where the damage is.

(3:30 – 3:43)

But if they’re all the way closed, the area is really bad. So the Waffle House Index is an informal metric used by FEMA just to gauge how bad a storm’s damage was to an area. They have red, yellow, and green.

(3:43 – 3:54)

Major companies like Walmart or Waffle House have great risk management teams. So they’re able to talk with the risk management and see what they need to do to prepare for storms. And that allows them to stay open during storms.

(3:55 – 4:11)

And that’s how the Waffle House got like their Waffle House Index is that they plan with the risk management how to prepare for storms coming in. They train their workers to know how to continue working in these conditions. They have alternative menus to use in case they lose access to fresh water or access to the electricity.

(4:12 – 4:25)

They have backup generators. And they bring in like tanks of fuel to power those generators. All of this allows them to only close when they absolutely need to, like when a storm is at its worst or when they have like a genuine concern for the worker’s safety.

(4:25 – 4:49)

How bad does a storm have to be before they bail out? Like, do they tell workers to go home beforehand? Or is it like an afterthought? Like the store or the restaurant is just absolutely wrecked. And so at that point, the workers don’t come in. Or does Waffle House and Walmart like know ahead of time to tell the workers not to come in? It’s a very well thought out process.

(4:50 – 5:05)

So they receive like extensive training on how to work in these conditions, as well as like the management has like this book of like things to do and to be checking on. But also corporate is like really involved in this. So they have like this war room that they set up where they bring in like extra TVs.

(5:06 – 5:16)

And they’re all in like their laptops. Like it’s something you would see out of like a political documentary where the president’s like in the war room deciding to like bomb somewhere. But it’s Waffle House deciding if their workers should be working or not.

(5:17 – 5:22)

It’s fantastic. There’s photos of it on Twitter. And it’s truly great.

(5:22 – 5:45)

So they bring in like meteorologists, IT specialists, plumbers, contractors, all kinds of people who are going to be there like to assess the damage and see how bad it is and at what point they need to like pull their workers out. If there’s going to be like a longer storm, they actually make these jump teams. So the jump teams are like volunteers from perhaps like the surrounding area that was unaffected.

(5:45 – 6:03)

So maybe like subdivisions around Houston, but not Houston itself. So these jump teams have volunteers on them that can work the Waffle House and get it open if they have to close and the workers who are supposed to be working there like need to go home to their families. Then they bring in outside Waffle House employees to come work it.

(6:04 – 6:10)

But it’s not just your average Waffle House employee either. They’re not asking people to like risk their lives. They actually bring in like their CEO to come work it too.

(6:11 – 6:15)

It’s like the high ups. Everyone is involved. It’s not like these plebeians working.

(6:15 – 6:34)

It’s everyone invested. It’s amazing. Like I’ve seen convoys of like the power company and you would just see what looks like half a mile of trucks, utility trucks from all these different utility companies and power companies going down the road and then staging just outside of the storm area.

(6:35 – 6:55)

So Waffle House has a convoy? I think to call it like a convoy is inaccurate. It’s more like they bring people from the outside close enough to jump in when help is like as soon as the roads clear, they’ll like switch out their jump team for the locals so the locals can like obviously they can go home to families when they want. Oh, that makes a lot of sense.

(6:56 – 7:03)

Yeah, because it’s so the Waffle House never has to close. Yeah, I guess if you’re in the impacted area, your home is probably maybe flooded. Yeah, yeah.

(7:03 – 7:28)

So they like the management of the local Waffle House like that’s going to be affected. They discuss with the workers ahead of time if they’re going to be able to work at all, if they need to stay home with their families as well as like if they need to stay home, they make a list of like the workers that might need extra help. So say like so say that there’s like three guys like Bobby, Daryl and like Jim and Bobby like he’s a single dad and he’s like two kids so he can’t work.

(7:28 – 7:36)

So then like make a note of that and maybe the manager will send like Daryl to go help Bobby with his kids in his house. It’s almost like a like a family community. It’s wonderful.

(7:37 – 7:58)

Just as a fun like tidbit with Katrina, it was one of the first ones that they really did this preparation for and it was one of their beginning stages. So every time there’s like a major hurricane or tornado or like anything Waffle House tries to improve its risk management. And with Katrina, they had to bring in like armed guards to guard their food and like fuel supplies that could keep serving people.

(7:59 – 8:09)

Katrina was an absolute mess. I don’t think I have anything positive to say about Katrina. So I was across the street from the Astrodome.

(8:09 – 8:23)

That’s where I lived at and that’s where they evacuated everybody to and nobody was prepared on either end of that. And it was just chaos. I did have quite a few uncles and aunts that lived there and they made it out.

(8:23 – 8:46)

But whenever you think about hurricanes, I’ve been through a few of them. But when you have absolute devastation, you have to think about the people and how important having things actually is. And so when my aunt and uncle moved in with my dad for a short amount of time after the storm because there was no going back to where they lived at.

(8:46 – 8:55)

But just little things like not having towels or toothbrush. At the beginning, think, oh, it’s just a towel. It’s just a toothbrush.

(8:55 – 9:06)

But then you have to like get a towel and then you have to get a toothbrush. And then you start realizing all the things that you need as a person. And then just everything up to that moment in your life is different.

(9:06 – 9:14)

From here on out, your life’s going to be different. And then they had a sister. So I guess it’s like an aunt-in-law.

(9:14 – 9:25)

So they lost their first house. They were in Chalmette there by New Orleans to Katrina. And then life goes on.

(9:26 – 9:37)

I guess it’s been quite a few years since then. And they had kids and the kids eventually had grandkids. And their kids and grandkids had gone back to Louisiana and had built a life for themselves.

(9:38 – 9:56)

And so they were going to move back to Louisiana, leave Houston area and go back to Louisiana. And right when they were selling their house, their second house got destroyed by a hurricane just a couple of years ago. Which one was that? Was that Ike? Uh, Ike and Harvey have both been pretty- Well, Harvey.

(9:57 – 9:59)

Yeah, it was Harvey. Yeah. If it was like in the last couple of years, it was Harvey.

(9:59 – 10:11)

Yeah, it was Harvey. Yeah. So Waffle House kind of promotes or not really promotes that they do this, but they like to say that by staying open, they provide a sense of like normalness, norm, normacy, normalness.

(10:11 – 10:15)

Normalcy. Normalcy. Thank you for the people who are affected.

(10:15 – 10:28)

But also like the rescue workers that get sent in, they’re a lot of times not locals. So they need somewhere to like sit and eat as well. So they like to pride themselves on being able to serve those like first responders.

(10:30 – 10:36)

So Waffle House has three levels that they operate at. They have green, which is a full menu. Everything’s like, okay, that’s what you normally see.

(10:36 – 10:51)

And a lot of times they can like continue operating at that, like during a, like Category 1 hurricane, there’s just going to be a lot of wind damage for the most part. After that, they have yellow, which is a limited menu. So at that point, electricity may be being provided by a backup generator.

(10:51 – 11:03)

Their food supplies may be low, or they may not have like ready access to running water, but they have stocks of like bottled water. They change their menu to accommodate that. If you Google this, actually, you can like find the different menus.

(11:03 – 11:13)

There’s like four different menus. There’s one for the backup generator, a green menu, low water menu. And then like a fourth one that I can’t remember what it is.

(11:14 – 11:20)

After that, you only have red. And so at that point, the Waffle House needs to close. That’s really, really bad.

(11:20 – 11:27)

Like I said, they try to stay open for first responders. Sometimes they’ll go to red and shut down for like the day. But then as soon as everything’s like clear, they’re sending their jump team.

(11:28 – 11:47)

But if it has to close normally by that point, FEMA knows the area has been like very badly affected. Did you learn anything about how long a Waffle House has stayed in the red? Yeah, there were some. I can’t remember if it was after Katrina or Harvey that they just never reopened.

(11:47 – 11:50)

It’s just like a permanently shut down. Yeah. Yeah.

(11:50 – 12:18)

It just wasn’t worth the investment to reopen. The flooding damage can be like so extensive that like once the integrity of like a building starts to be compromised, a lot of times a business or a family won’t continue to invest in it because the amount of money it would take to just replace like a foundation or like the beams that hold it is too much. So what’s the average time then for a standing Waffle House to reopen once it hits the red? I don’t know.

(12:18 – 12:22)

It’s going to depend on like the storm. So I don’t know. That makes a lot of sense.

(12:22 – 12:35)

Yeah. Like I said, they have their war room set up. So like the CEO and the chair, like all of these people are there actively deciding when is it safe for our workers to be there, when do we need to pull them out, when do we need to send the jump team in.

(12:35 – 13:11)

Their utmost concern is like the worker safety and then providing to the community as best they can. So Hurricane Dory and the most recent hurricane caused a couple Waffle Houses in South Carolina to hit the red and close and Hurricane Harvey in 2017 caused I think six Waffle Houses in Houston to hit red and close even though Hurricane Harvey was only a Category 4. So you might think that- Only a Category 4. Only a Category 4 as compared to a 5. Like I’ve been through a 3 with Hurricane Alicia and that was pretty intense. What year was that? 1983.

(13:14 – 13:28)

Yeah. So like when Dorian hit, what was it, the Caribbean, it was at a 5. So it was like an obvious red. But people might be assuming that because Waffle House put so much like planning and infrastructure and like risk management into staying open that they might only be closing in 5s.

(13:29 – 13:42)

But it’s not really. The category only has to do with the wind damage occurring, like the speed at which hurricane is moving out. Like I said earlier, one of the big reasons that Waffle Houses or like businesses in general will close during a hurricane is more so about the flooding.

(13:43 – 13:53)

So the categories just refer to the speed that the wind is moving at. It’s not about like the amount of flooding that’s going to occur. So hurricanes are getting worse.

(13:54 – 14:12)

By worse, I specifically mean they’re getting more intense. The frequency at which hurricanes are occurring isn’t increasing per se, but hurricanes are projected to get more intense as global warming increases. But I saw on the news, our president said he’s never seen a Category 5 before.

(14:13 – 14:23)

We have had several Category 5 hurricanes during his presidency. Did they all hit Alabama? No, no, no. No, they haven’t been hitting Alabama.

(14:23 – 14:42)

I don’t, when was the last time we had one hit Alabama? Like the actual hurricane, not like the storm portion, but like the actual hurricane. Because once it like makes land, it’ll weaken and continue like going up. And so you can get like the remnants of a hurricane up in like Idaho, but it’s not the actual hurricane.

(14:42 – 15:02)

Is that the Sharpie line? That is not the Sharpie line, sir. Sharpie gate. Why? This is not the time to get into that.

(15:02 – 15:13)

We can talk about it later. So hurricanes are expected to get more intense as global warming increases. This is because the real fuel for like hurricanes is heat.

(15:15 – 15:22)

So heat is just a form of energy. And so it’s like a fundamental law that energy doesn’t ever like disappear. It just gets like transferred to other things.

(15:22 – 15:35)

So as the oceans get like warmer, they’re just taking this energy. And as the air gets warmer, they’re just like taking this energy and that provides more fuel for hurricanes. So global warming is making hurricanes more intense through a couple of ways.

(15:36 – 15:59)

There is an increase in the sea surface temperature, which like I said, is providing more fuel for the hurricanes. If you like need an example for that, Katrina was not like weak per se before it hit the Gulf of Mexico, but it got notably stronger because all that warm helps it go like faster. Well, the Gulf of Mexico is shallower, right? So it’s going to be warmer than the Atlantic.

(16:00 – 16:03)

Yeah, yeah. It’s going to be it’s shallower. So it’s going to be warmer than the Atlantic.

(16:04 – 16:17)

But the problem is as global warming increases, the overall surface temperature of like water is getting higher. So it’s holding more energy, which is going to add more fuel for hurricanes. So it’s like not a problem that’s exclusive to the Gulf of Mexico.

(16:17 – 16:24)

It’s happening overall. Including in like the Pacific. So it’s not an isolated event.

(16:27 – 16:45)

Another problem that’s occurring is as global warming increases, like the ice caps are melting, so it’s going to make the sea levels rise. Higher sea levels are going to give like a higher baseline for storm surges to occur. A storm surge is just the initial surge of water from the ocean onto a coast before the hurricane actually hits.

(16:45 – 16:55)

So the pressure causes all the water to like be forced towards the coast. That’s where a lot of the damage and deaths actually occur. Well, a hurricane is a low pressure system, right? So it’s- Yeah.

(16:55 – 17:07)

Did I? Explain that wrong? No, no. You’re just explaining how there would be like a- Like it’s the pressure change that causes it. Like a higher water, like a ring of higher water in front of the hurricane.

(17:07 – 17:13)

Yeah, yeah. It’s like if you just like, if you like push on jello, everything goes like out from where you pushed. The same thing happens with a hurricane.

(17:14 – 17:41)

If your finger is the hurricane and the jello is the water. So in Hurricane Katrina, at least 1500 people died with the cause kind of being the storm surge, whether it was like direct or indirect, it can be linked back to the storm surge. How many people died in Katrina total? Do you remember? No, I don’t remember.

(17:41 – 17:50)

I know the storm that had the highest death toll for people was the 1900 storm that hit Galveston. Yeah, that one was wicked. It was a 8,000.

(17:50 – 17:59)

8,000 people died in that one. Right, yeah. So the official numbers would be 8,000, but I’ve seen numbers that were close to 12,000.

(17:59 – 18:04)

Yeah, yeah. I’ve seen that too. And it was the storm surge that came through and there was another town.

(18:05 – 18:19)

We don’t even see it on the maps anymore called Indianola. It was hit by a hurricane not long before that one and it decimated the city. But everybody returned back to it and then it got hit by another hurricane.

(18:19 – 18:26)

And now it’s not there anymore. There is no Indianola, Texas. And so the people aren’t stupid.

(18:26 – 18:32)

They were like, well, we’re here on Galveston. It’s essentially just a big sandbar. Maybe we need a seawall.

(18:32 – 18:36)

Yeah, yeah. They built a seawall after that. After, but they wanted it beforehand.

(18:37 – 18:44)

And their meteorologist was saying, no, it’s not going to hit. We’re not going to get a hurricane to hit Galveston. And so they didn’t build the seawall.

(18:44 – 18:54)

And then the storm surge hit with that 1900 storm and it killed all of those people. Now there’s a seawall. In fact, they’ve added onto it.

(18:54 – 19:05)

Yeah, they have the seawall. And didn’t you tell us once that when we went to Galveston to tour UTMB, you told us that they raised the city in essence, right? Yeah, yeah. If you look at the large buildings there.

(19:05 – 19:12)

Oh, yeah, yeah. I remember reading about that. So they were only a couple meters higher than sea level when the storm surge initially happened.

(19:12 – 19:24)

And then after that, they raised it like 10 meters or something. Just so hopefully when another storm surge occurred that it would not be able to hit them. So when you look at those buildings, those aren’t basement windows.

(19:24 – 19:27)

That used to be the first floor. Right, right. They backfilled it in.

(19:27 – 19:32)

Yeah, okay. Yeah. Houston had the same thing after, I think, Ike.

(19:32 – 19:40)

They had a vote as to whether they would build a better system. I guess like levees to help block the water from coming in. And they voted to not.

(19:40 – 19:52)

And then less than 10 years later, they get hit by Harvey. Yeah, we’ve had flooding in Houston before. There was a tropical storm, Allison, that came and it just lingered.

(19:52 – 19:58)

So it wasn’t really about wind. It was just the amount of rainfall. And it wasn’t progressing out of the region.

(19:58 – 20:06)

So it was just kind of stalled there. And it just started raining for many, many days. And everything flooded.

(20:06 – 20:15)

I know the lab I worked in flooded. Baylor College of Medicine and others in the Texas Medical Center flooded. And they used to have the animal labs down there.

(20:16 – 20:26)

And so after the fact, they went and built walls and pumps. They lifted the generators up off the ground. They moved the animal labs so it would never happen again.

(20:26 – 20:32)

Was the animal lab at ground level and they raised it up or what? It was underground. Oh, God. It was in the basement.

(20:33 – 20:39)

Oh. Did they drown? Yes. Yeah.

(20:39 – 20:54)

A lot was learned about that. That’s a bummer. There are cities and countries in Asia that get really bad, like typhoons and cyclones there too.

(20:55 – 20:58)

Cyclone? Cyclops. Cyclone. Cyclone.

(20:58 – 21:04)

Cyclone. Thank you. And so they’ve done way better to manage these storms as they come.

(21:04 – 21:13)

I don’t really know why Houston isn’t making that same effort. But they’ve had the votes to do it and they keep turning it down. Well, it’s progress.

(21:14 – 21:30)

And so whenever a hurricane hits, they’ll go and they’ll look at the damage. And then they’ll kind of district it. And so when something gets damaged, they’ll be like, well, in the future, these buildings need to have this level of architecture.

(21:31 – 21:51)

Perhaps they should go back to thinking about the proposed levy system, only because hurricanes are projected to get more intense, particularly through their rainfall. So it was extremely problematic with Harvey was the amount of unprecedented rainfall that occurred. The National Weather Service actually had to add two more darker shades of purple to compensate for the amount of rain that they were receiving.

(21:51 – 21:59)

Because an amount like that had never happened before. It wasn’t something we had seen. It wasn’t something that we were like, I’m sure it was a thought, but it wasn’t anything that we really thought about.

(21:59 – 22:06)

It was just a distant thought. What if this happened? It ended up happening. They had to add the extra colors just to show people how bad it was.

(22:08 – 22:28)

So currently, scientists and meteorologists are arguing over whether a new category needs to be added for the super intense hurricanes that are beginning to occur and projected to continue. Currently, we have Category 1 hurricanes, which are 74 to 95 miles per hour wind speeds. Category 2, which is 96 to 110 miles per hour wind speeds.

(22:28 – 22:40)

Category 3, which is 111 to 129 miles per hour wind speeds. Category 4, which is 130 to 156. Category 5, which is 157 onwards.

(22:41 – 22:54)

But we’re only getting worse and worse hurricanes. Obviously, there’s always going to be one that we’ve never seen before, but these super intense ones are getting more common. So they’re arguing over whether they need to add a sixth category to compensate for these super strong ones.

(22:56 – 23:09)

So as hurricanes get more intense, they’re more likely to cause flooding. Hurricanes causing flooding is problematic because standing water is known to increase mosquito populations. After Hurricane Harvey, Houston did like up their mosquito control measures.

(23:10 – 23:20)

What do they do for that? I know there’s like mosquito fish that they can put into pools. There’s chemicals that they can spray from trucks. Is there anything in addition they do? Yeah.

(23:20 – 23:28)

So I was reading primarily that they were like spraying pesticides, like from airplanes. That was the primary thing. From an airplane? Yeah.

(23:28 – 23:33)

Yeah. Well, they’d have to like miss the whole city. Any stagnant water mosquitoes will like find and breed in.

(23:33 – 23:37)

No, that makes a lot of sense. I just, wow, I didn’t think about it. Yeah, no, no.

(23:37 – 23:44)

They have like the whole city to like compensate for. Right, because you probably can’t drive down these roads. And so you would need to go by air.

(23:44 – 23:58)

Yeah, they’re swampy, but then just little puddles that are going to like form in people’s yards need to be addressed too. Or you’re going to have like outstandingly large mosquito populations. And West Nile virus is known to circulate like within the mosquitoes in Houston.

(23:58 – 24:11)

So they needed to get rid of them. So I guess something that just a normal person can do is just look outside and if you have like a bucket of water, go ahead and empty it out or just look for anything where water might be standing in afterwards. Yeah, you can do that.

(24:12 – 24:19)

But the issue with the flooding is the soil is so super saturated. Even if you do that, like it may not go anywhere. The water may just continue in like your grass.

(24:21 – 24:42)

So storms kind of get, or not storms, natural events such as like hurricanes and earthquakes and tornadoes kind of get this unfair perspective that they’re contributing to disease outbreak. And they are in a way, but not in the way that people think. Some people think like if you see a dead body from someone who drowned in the hurricane that they’re like actively spreading disease in the water.

(24:42 – 24:58)

And that’s not necessarily true. The outbreaks from hurricanes and earthquakes and things tend to be more from unsanitary conditions caused by massive amounts of population displacement. Thank you.

(24:58 – 25:22)

My mind like it left. So specifically their proximity to safe water and functioning bathrooms, the nutritional status of the population, their level of immunity to vaccine preventable diseases and access to healthcare, like the primary factors that need to be considered as to whether an outbreak is going to occur. So like, obviously you want people to be immune to measles.

(25:22 – 25:38)

So you want to have like a vaccinated population. If they’re not having access to healthcare, they’re not going to know like when something’s wrong. Their nutritional status, if you are already malnourished, then like when you get sick, it’ll have a much harsher toll on you than it would have if you were like eating your vegetables.

(25:38 – 26:01)

And these people that are displaced don’t always like have the opportunity to do that. But what I want to talk about is proximity to safe water and functioning bathrooms. So- Before that, I’ve heard of cases, it may have been with Haiti, in which some of the disease outbreaks actually occur from volunteers coming to there to help out, to actually bring a pathogen in with them.

(26:02 – 26:32)

I didn’t read about that, but it would make sense in the same way that like the same thing happened with like America, whenever Columbus and them came, you can transmit. So like if a population doesn’t have an acquired immunity, and they haven’t been exposed to like a pathogen, someone brings it in, it’s entirely new, the population will be like heavily hit. I don’t remember specifically what, but I do remember Haiti after their 2010 earthquake reading that they had a lot of outbreaks.

(26:32 – 26:51)

I remember like news about it, how just like horrible and like sick the people were because they didn’t have access to like clean water and bathrooms. And so in those conditions, it like allows a lot of like fecal-oral diseases to just like thrive. What kind of fecal-oral diseases? In Haiti? Yeah.

(26:51 – 27:15)

What is a fecal-oral disease? Okay. So a fecal-oral disease is a like infection that occurs typically through the consumption of something that’s contaminated with like fecal matter. So it’s not from like ****, it’s more from someone like wiping and not washing their hands or, I mean, you could probably catch something that way, but that’s not the primary way that people are catching things.

(27:16 – 27:36)

It’s more so like so in like an underdeveloped nation, they might be dumping their sewer into the river they’re also pulling water from. So that’s where a lot of your fecal-oral diseases are thriving. What’s an example? One fecal-oral disease that I am particularly intrigued by is cholera.

(27:37 – 27:58)

So following Hurricane Katrina, there were two cases of Vibrio cholerae confirmed in Louisiana. While those cases were attributed to undercooked seafood, cholera is something that public health and CDC officials keep a lookout for following flooding and hurricanes. So cholera is an acute diarrheal infection caused by the bacteria Vibrio cholerae.

(27:59 – 28:12)

Cholera is an extremely virulent disease that can cause watery diarrhea, vomiting, muscle fatigue, and death. Virulent just means like how severe the disease is. And it takes between 12 hours and 5 days to show symptoms after ingesting the bacteria.

(28:14 – 28:40)

The disease occurs through fecal-oral transmission, which is where you ingest like food or water contaminated with fecal matter or it’s environmentally acquired. There are roughly 1.3 to 4 million cases of cholera per year worldwide and roughly 21,000 to 143 deaths. It’s relatively rare in the US, but it’s like endemic in other populations throughout the world.

(28:42 – 28:56)

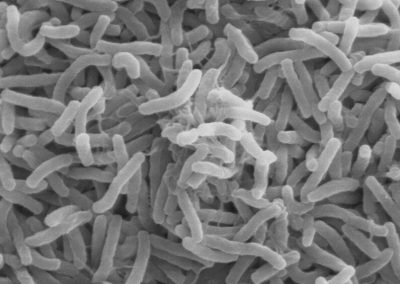

Vibrio cholerae is a gram-negative comma-shaped bacterium. Gram-negative just means that a bacteria has an inner membrane and then a cell wall and then an outer membrane as compared to a gram-positive bacteria that has an inner membrane and then a cell wall. So no outer membrane.

(28:57 – 29:11)

Did you say it’s comma-shaped? I always thought it looked like one of those puffy Cheetos. Yeah, yeah. It’s like a bit larger in ratio than a comma.

(29:11 – 29:26)

You could describe that as increased girth, but the length increases too. It just reminds me of a puffy Cheeto with a long tail on it. That’s an accurate description.

(29:26 – 29:45)

I always think of jelly beans just because it’s more fun, but a tailed Cheeto is fine. It’s a facultative anaerobic, meaning it can live in an aerobic environment as well as an anaerobic environment. So this means that it can survive in oxygen-containing or lacking oxygen environments.

(29:45 – 29:59)

It was first isolated in 1854 by Filippo Puccini and then again by Robert Koch in 1884. Also in 1884 and around the 1850s was the big

Credits

Written and performed by Dr. Dustin Edwards and Faith Cox

Music from https://filmmusic.io

“Bossa Antigua” by Kevin MacLeod (https://incompetech.com);

license CC BY 4.0

Images from

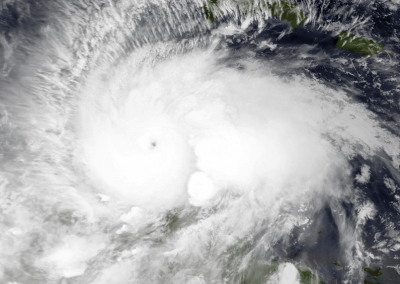

Hurricane Matthew © NOAA; public domain

Vibrio cholerae © Kirn, et al; public domain