Hell on Weils

How does Mardi Gras and Carnival connect to leptospirosis? From New Orleans parades to Brazil’s Carnival, uncover the link between reservoirs, Leptospira bacteria, and the hidden dangers lurking in water and soil.

From Mardi Gras to Microbes: How Festivals, Animals, and Disease Are Connected

Festivals like Mardi Gras and Carnival are known for their extravagant parades, music, and vibrant celebrations. But beneath the revelry, these large gatherings can also reveal fascinating connections between human culture, the environment, and infectious diseases. A closer look at events in New Orleans and Brazil uncovers unexpected links between festivities, animal reservoirs, and microbial threats.

A City of Celebrations and Surprises

In New Orleans, Mardi Gras brings together locals and tourists in a whirlwind of parades, beads, and king cakes. In 1997, the city’s festive energy was amplified by Super Bowl 31, creating a weeks-long party atmosphere. However, beneath the surface of this celebration, another presence lurked—New Orleans’ infamous rat population, which, as recent studies suggest, may carry dangerous pathogens, including leptospirosis. This connection between urban wildlife and human health serves as a reminder that infectious diseases can emerge from unexpected sources.

Carnival, Yellow Fever, and the Silent Jungle

The connection between celebrations and disease isn’t limited to New Orleans. In Brazil, the grander spectacle of Carnival draws millions to the streets of Rio de Janeiro, where the festival’s name—derived from Carne Vale, or “goodbye meat”—signals the beginning of Lent. However, in 2007-2008, something unusual happened in Brazil’s forests: howler monkeys, known for their deafening calls, began dying en masse. The sudden silence in these jungle regions alerted scientists, who discovered that the monkeys were dying from yellow fever. Recognizing this as a warning sign, public health officials acted swiftly to prevent mosquitoes from spreading the virus into highly populated metropolitan areas.

The Canary in the Coal Mine: How Animals Signal Outbreaks

The concept of animals serving as early indicators of environmental dangers isn’t new. Historically, coal miners used canaries to detect toxic gases, as the small birds would show signs of distress before humans could sense the danger. This idea extends to modern epidemiology, where unusual animal deaths can signal the spread of infectious diseases. In 1999, large numbers of dead crows in the U.S. led scientists to identify the arrival of West Nile virus in New York City. Similarly, rodents may serve as a warning system for leptospirosis, a bacterial infection that thrives in warm, wet environments and spreads through the urine of infected animals.

Understanding Reservoirs: Where Pathogens Hide

Pathogens often persist in specific animal or environmental reservoirs before infecting humans. These reservoirs can be classified into three main types:

- Animal reservoirs: Some animals, like sheep, harbor bacteria such as Bacillus anthracis (which causes anthrax) without showing symptoms.

- Environmental reservoirs: Water or soil can serve as a breeding ground for microbes like Leptospira, which causes leptospirosis.

- Asymptomatic carriers: Humans can unknowingly spread infections without experiencing symptoms, as seen in cases like Typhoid Mary.

Leptospirosis: A Hidden Threat

Leptospirosis, also known as Weil’s disease, is one of the most widespread zoonotic infections. Caused by Leptospira bacteria, it is commonly found in tropical and temperate regions and spreads through the urine of infected animals. While most infections are mild, severe cases can lead to kidney failure, liver damage, or even death. The disease is particularly concerning for individuals exposed to contaminated water, such as farmers, veterinarians, and outdoor enthusiasts.

From Festivals to Global Health Awareness

While Mardi Gras and Carnival are often seen as moments of joy and cultural expression, they also highlight the intersection of human activity and the microbial world. Urban environments, animal populations, and large gatherings create opportunities for disease transmission, reinforcing the importance of monitoring wildlife and environmental health. Just as scientists used howler monkeys to track yellow fever and crows to identify West Nile virus, continued surveillance of animal populations could help prevent future outbreaks.

As the world becomes more interconnected, understanding these links between culture, animals, and microbes will be crucial in mitigating the risks of infectious diseases. So, the next time you raise a glass at Mardi Gras or dance to samba during Carnival, remember that human history is often intertwined with the unseen world of microbes.

Show Notes

(0:00 – 0:33)

I was working in New Orleans one year that had both Super Bowl 31 between the Packers and the Patriots and Mardi Gras happening all within just a couple of weeks of each other. The entire city had like that energetic party atmosphere like the whole time. People were wearing those yellow cheese head hats for the Super Bowl game and there was just a couple weeks later everybody was all in for Fat Tuesday with the parades and the floats and the beads and king cakes and everything was just dressed up in purple and yellow and green.

(0:34 – 1:20)

Unfortunately for us, we were on night shift the whole time and so we missed almost all of it. But I do remember one morning we had just finished this 12-hour shift and it was about 7 a.m. and we decided to head out to the historic French Quarter for dinner, breakfast, breakfast, dinner and kind of try to enjoy the atmosphere for about an hour before we had to like head back to the hotel for a little bit of rest and get ready for the next 12-hour shift. Well, there was this news crew, morning news crew, that was out interviewing people in the streets and they came up to our table and, you know, we were having some drinks at dinner and they were trying to make like this big deal about how this town was just like a big party town and everybody was up partying all day and all night including having alcohol at breakfast.

(1:20 – 1:32)

And they were asking us about who we were rooting for the Super Bowl and I of course said, you know, the Patriots. And then the woman goes, cut. So, I guess they were from like a Boston News crew.

(1:33 – 1:47)

Speaking of New Orleans, I came across this article about how the rats in New Orleans are apparently like carrying a lot of pathogens including leptospirosis. Must be a lot of fun at parties. I’m Dr. Dustin Edwards.

(1:47 – 2:01)

And I’m Faith Cox. Welcome to Germomics where we go to B from A in the most roundabout way. A mix of microbiology and history, in this series we connect different aspects of modern life and society to microbes through seemingly unconnected natural events, discoveries, and inventions.

(2:01 – 2:16)

How else does Mardi Gras connect to leptospirosis? Let’s find out. In Brazil, the party continues on a much grander scale with Carnaval. The festival’s name comes from the words Carne Vale, which translates to goodbye meat.

(2:16 – 2:36)

The term Carnival has been used to indicate the start of Lent. Here are the beaches of Rio de Janeiro in the southern part of Brazil. It’s a huge metropolitan city about the size of New York where there are much bigger parades, floats, very elaborate costumes, performers.

(2:36 – 2:53)

I’ve seen some videos there where there’s always those people with the flames on a stick, twirling the flaming stick. And the elaborate headdresses that go like seemingly like three or four feet into the air, lots of feathers. And of course, samba music playing everywhere.

(2:56 – 3:17)

However, in 2007-2008 in the forest of Brazil, there was silence. When they gave warning to millions of people that fill these cities, the normally raucous howler monkeys began to die off in mass. And so, these very loud forested areas had become quite silent, which alerted officials that there may be something up.

(3:17 – 3:46)

And so, they went and tested the howler monkeys and found that they were positive for yellow fever. So, they were able to take steps to try to stop mosquitoes from entering into the metropolitan areas carrying yellow fever with them, yellow fever virus with them. Officials took notice and were able to detect yellow fever spreading among the monkeys, which allowed them to take preventative measures to try to stop mosquitoes from carrying the outbreak to the highly populated metropolitan areas.

(3:48 – 4:21)

There’s this concept called the canary in the coal mine. So up until only about 1986, miners used to take birds into the mines with them as a way of trying to detect toxic gases that might be present because the birds being so much smaller, if they were to inhale these gases would die or look distressed. So, the miners would keep an eye on these birds and if they saw one kind of fall over in the cage or stop singing, it would alert them that they may need to evacuate that there might be poisonous gases present within the mine.

(4:23 – 4:47)

This leads to the saying canaries in the coal mine, which is used to describe a number of different types of early warning systems. Another example of using wild animals as a canary in a coal mine is in 1999 when crows were dying in these large groups and medical officials were able to determine that West Nile virus was making its way towards New York City. I read a paper that mentioned that this week.

(4:47 – 4:57)

The paper was titled, I’m not going outside until I can check on my gerbil. It was published about 10 years ago. What was it called? I’m not going outside until I can check on my gerbil.

(4:57 – 5:18)

It was published in the Lancet, Infectious Disease. So, it was like why I clicked on it because the title is like a bit wacky to be in the Lancet. The paper suggested that epidemiologists, so scientists that track disease progression, are underutilizing animal populations to survey for pathogens as they may potentially be serving as reservoirs for a disease before they infect humans.

(5:18 – 5:35)

So, examples being like what happened with the crows or the monkeys in Brazil. Reservoirs are a population or a specific environment in which a pathogen is able to live in and reproduce. Something can act as a reservoir by being colonized but it may not have an infection per se.

(5:36 – 5:56)

So, colonization is simply when a microorganism is reproducing in or on a host versus an infection which is when there’s the actual invasion of host tissues and causing tissue damage. So, you have like all these microbes that live on your skin and they colonize you but you’re not infected by them, you’re just a host. So, you’re just a reservoir for those.

(5:56 – 6:04)

There are three main types of reservoirs. Animal reservoirs, so animals that harbor the microorganism. So, an example would be like sheep.

(6:04 – 6:33)

They are colonized by the bacteria that causes anthrax but they don’t have like the symptomology of an anthrax infection. So, there are animal reservoirs and environmental reservoirs which are just like water or soil that the microorganism is reproducing in. But there’s also asymptomatic carriers which is a term typically used to refer to a human who’s colonized with a microorganism and can transmit the organism to others despite not having an infection themselves such as typhoid Mary.

(6:35 – 7:12)

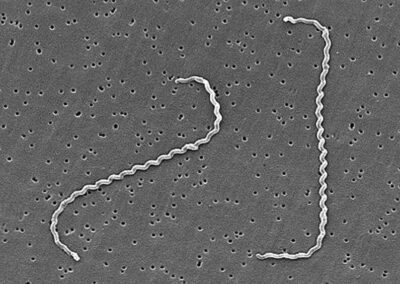

So, the author of the gerbil paper’s consideration was that rodents could be acting as reservoirs for leptospirosis being like the canaries in the coal mine for wheel’s disease which can also be said as veal’s disease with like a v sound since it was initially discovered by a German physician. This illness is caused by the bacterium Leptospira borgpetersenii which is a gram-negative aerobic spirochete. So gram-negative meaning that it has an inner membrane, a cell wall, and then an outer membrane, aerobic meaning that it lives in oxygenated environments, and then spirochete being that it’s this little small really like kinky curly bacterium.

(7:13 – 7:54)

Looks like a jack-in-the-box curly fry. It does, yeah. I haven’t heard that description before.

It’s entirely true though. So, the group of bacteria are further broken down into serovars which are based on the variations of lipopolysaccharide which is a protein on a bacterial cell wall. Lipopolysaccharide can also be abbreviated by LPS and it’s an endotoxin so it’s a toxin on the cell wall of the bacteria.

It never becomes detached but it is often what’s recognized by immune cells so they know that there’s an infection. Wheel’s disease is also known as leptospirosis and is considered the most widespread zoonotic infection. The infection can affect humans and other mammals.

(7:55 – 8:18)

The bacteria are commonly found in tropical and temperate climates, temperate climates just being those climates found between the equatorial zone and the poles so like the U.S. would be an example of a temperate climate. The bacteria are spread through the urine of infected wild and domestic animals so hence the author’s concern about his gerbil. And the bacteria can survive in soil and water with those being environmental reservoirs.

(8:19 – 8:39)

As a result, infection can be more common among kayakers, canoers, rowers, or occupational workers so those who might be working with the domestic animals such as a farmer or a veterinarian. Leptospirosis is considered an emerging infectious disease. It’s estimated there are more than 1 million cases worldwide and about 59,000 deaths.

(8:39 – 8:59)

In the U.S. specifically though, there’s only about 100 to 150 cases with about 50% of those occurring in Puerto Rico. About 90% of the infections are self-limiting, meaning they seem to resolve themselves within the patient and they aren’t that big of a deal. They’re so minor that patients might think they just have a cold or the flu so they might not even go to the doctor.

(9:00 – 9:22)

However, about 10% of those cases progress to more severe symptoms. So, the infection itself might be biphasic in the patient, so meaning it may have a first phase and a second phase. So, for the first phase, that’s when patients might have the mild flu-like symptoms that make it really hard to distinguish from other febrile or fever-causing infections in the first phase.

(9:23 – 9:48)

And so, the majority of patients just go to this phase and then they recover and it’s really not that big of a deal. The second phase that not everyone progresses to has much more severe symptoms. So, at that point, a patient may present with abrupt fever onset, a headache, muscle aches, vomiting, and or diarrhea, and jaundice, which is the yellowing of the eyes and skin due to kidney failure.

(9:49 – 10:23)

These severe cases are the majority of the diagnosed cases because that’s the point that people need help at is once it starts getting really severe. And then of those more severe cases, they may further progress into what’s actually true severe leptospirosis, which is a high mortality syndrome with multi-organ involvement. At that point, you’re presenting with kidney failure, liver failure, pulmonary hemorrhage, which is bleeding in the lungs, or with meningitis, which is the swelling of the meninges, the protective membranes around the brain and the spinal cord, a place you absolutely do not want swelling.

(10:24 – 10:43)

Patients may have a laboratory-diagnosed leptospirosis infection through three different methods. There’s PCR, which is when they amplify the bacteria’s DNA from a patient’s sample. Or they can do an antibody test to see if the patient has an active immune response against the bacteria, which they would only have if they’ve had prior exposure.

(10:44 – 11:06)

Or they can try to isolate the actual bacteria from a clinical sample of the patient, like a urine sample. There is preventative treatment for leptospirosis, so there are vaccines available for animals and pets. There’s not a vaccine approved for human use in the U.S. Less severe leptospirosis infections may be treated with oral antibiotics like doxycycline or amoxicillin.

(11:07 – 11:24)

More severe infections may be treated with IV administration of the same antibiotics. So, to recap, we talked about Mardi Gras and Carnival, Canaries in a coal mine, rodents as reservoirs, and leptospirosis. Thank you for listening to episode 9, Hell on Wheels.

(11:24 – 11:47)

Show notes, citations, transcripts, and social media links are available on our website at germomics.com. So earlier this week, I learned that gerbils are banned as pets in California. Banned? Banned, like a hard ban. So apparently, health officials were concerned that the natural climate of California was too close to the climate of gerbils, like where they originate from.

(11:48 – 12:03)

And so, the concern was that if some gerbils were ever to escape, or if people release them into the wild as they do with their pets sometimes, that they would establish a feral population of gerbils. And so, I like to think about all the gerbils rising up against the state of California to fight. It’s more than likely they are concerned about there being an invasive species.

(12:04 – 12:15)

It’s like Planet of the Apes, but gerbils. But gerbils. But that’s dramatically different than Texas’ approach, which is to have just like all kinds of animals.

(12:17 – 12:29)

I read a while back there were more captive tigers in Texas than there are wild tigers in India. When I was a kid, for Christmas, I always asked for an elephant. Wow, really? Yeah.

(12:30 – 12:39)

And I remember one, I think I was four years old. I know I was four years old. I asked for an elephant or a purple like semi-truck.

(12:39 – 12:58)

There was like no chance that I was going to get either. In fact, you probably had a better chance of finding an elephant in Texas than a purple… Toy semi-truck? Toy semi-truck. And so, what my dad did was he painted the trailer this really thick layer of purple paint.

(13:00 – 13:13)

But something I noticed later on was that there was a distinct thumbprint on the back corner. So, they kind of gave it away that my dad had painted it. It was the best present ever.

Credits

Written and performed by Dr. Dustin Edwards and Faith Cox

Music from

“Main Stem” by U.S. Army Blues; license CC 1.0

“Modern Jazz Samba” by Kevin MacLeod; license CC BY 4.0

Images from

Carnaval Queen © unknown; license CC BY-SA 4.0

Leptospira © Janice Haney Carr, CDC; public domain