Rabies Day Out

How does the Google no internet Dinosaur Game connect to Rabies? Haunt over the Raven by Edgar Allen Poe, classic Universal monster movies, psychological thriller and horror by Hitchcock, Kubrick, and Stephen King – including Cujo, and rabies and post exposure vaccine treatment.

Show Notes

(0:00 – 0:10)

This week was probably one of the most impressive lightning storms I’ve ever seen. How did you guys fare? Oh, we lost, um, tree limbs. It was really windy over in our, like, area.

(0:10 – 0:29)

Did you lose power? Yeah, we lost power several times. We actually, um, we have this old kerosene lamp that we have for times that we lose power, and I had an exam the next day, so I had to study, like, by my lamplight to be prepared for my exam. Yeah, I lost internet too, and so I played the Google dinosaur game.

(0:29 – 1:10)

I love the dinosaur game. Yeah, so I was playing the dinosaur game, and Halloween’s coming up, and I was thinking, I really want to be one of those inflatable T-Rex costumes, but I can’t because my girls keep choosing to be superheroes, so we’re there being Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel this time, but I can think of at least, like, four different reasons, or four different times I can wear that dinosaur costume outside of Halloween. Oh, have you tried to convince them to be dinosaurs with you? Yes, I think dinosaurs are cool and everything, but I guess not as cool as superheroes, so I’m thinking next year I’ll just get the T-Rex costume and just wear a cape.

(1:10 – 1:19)

I’m Dr. Dustin Edwards. And I’m Faith Cox. Welcome to Germomics, where we go to B from A in the most roundabout way, a mix of microbiology and history.

(1:19 – 1:39)

In this series, we connect different aspects of modern life and society to microbes through seemingly unconnected natural events, discoveries, and inventions. I think the first time I ever lost internet access to, like, government websites was during the shutdown in 2013. I was actually giving my very first lecture on rabies, and I tend not to use textbooks.

(1:39 – 2:04)

I tend to use either government websites or primary literature, and for those lectures, I took a lot of screenshots of these government websites that were just shut down. So if you go to the FDA or the CDC or the NIH, they all had, like, I’m sorry pages. But I have kept screenshots and put them on my lecture slides as kind of a reminder that you can’t just rely on the internet for information.

(2:05 – 2:24)

So how else does Google’s no-internet dinosaur game connect to rabies? Let’s find out. Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered weak and weary over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore. While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping, as of someone gently wrapping, wrapping at my chamber door.

(2:25 – 2:40)

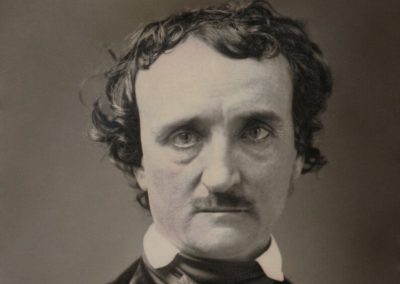

To some visitor I muttered, tapping at my chamber door. Only this and nothing more. The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe is probably the most well-known of the gothic fictions that have been written.

(2:41 – 3:04)

Edgar Allan Poe also wrote The Cask of the Amontillado, The Telltale Heart, and other horror short stories. He also developed the genre of the detective novel, and so if you’re into reading kind of like murder mysteries or Sherlock Holmes style books, so he was one of the creators of that. He died at the age of 40.

(3:04 – 3:37)

He was found wandering a bit senselessly around the streets of Baltimore, and he died, possibly from rabies. An interesting tidbit about Edgar Allan Poe is that in 1949, on the 100th anniversary of his death, there was this mysterious toaster. So a person dressed all in black with this broad brimmed hat, and this white scarf would come and visit his gravesite every year, and he wouldn’t talk to anybody.

(3:38 – 4:08)

And he would have a drink of cognac and leave the empty bottle there, as well as leaving three roses. This tradition would continue on until 2009, on the 200th anniversary of his birth. Inspired by these gothic fiction writers, such as Edgar Allan Poe, and Mary Shelley, and Bram Stoker, in the 1920s and 30s, all the way up until the early 1940s, Universal Pictures began what would be a classic era in monster movies.

(4:08 – 4:33)

And they started with these silent films, and then eventually started adding sound in, in order to try to create some suspense. And this was an important moment for society, because we were going through the Great Depression, and this gave people a momentary escape from the problems in their lives. There was a trilogy of Poe stories at the beginning of this monster movie era.

(4:34 – 5:05)

The first was The Murders in the Rue Morgue in 1932, starring Bela Lugosi. And this was followed by The Black Cat and The Raven in 1935. A hallmark of these movies was that they starred a trio of actors, Bela Lugosi, Boris Karloff, and Lon Chaney Jr. These actors would go on to play in the most well-known movies that, when you go trick-or-treating later on, that you would kind of recognize their characters.

(5:05 – 5:27)

These would be the movies The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Phantom of the Opera, Dracula, Frankenstein, The Mummy, and The Wolfman. In the 1950s, different subgenres of horror became popular. In the midst of the Cold War, movies with mutants such as Godzilla appeared, warning against the dangers of a nuclear world.

(5:28 – 5:41)

Psychological and thriller or suspense horror movies gained more importance. There was Alfred Hitchcock, who would be considered by many the master of suspense. He began with silent films in the 1920s and really honed his craft through the 1930s and 40s.

(5:41 – 6:02)

He directed Dial M for Murder in 1954. And by 1960, Hitchcock had directed four films, often ranked among the greatest of all time. Rear Window in 1954, Vertigo in 1958, North by Northwest in 1959, and Psycho in 1960, and one that I’m personally fond of is The Birds in 1963.

(6:03 – 6:11)

There was also Stanley Kubrick, who in 2001 directed A Space Odyssey. I’m sorry, Dave. I can’t do that.

(6:12 – 6:37)

Um, Stanley Kubrick also directed A Clockwork Orange and The Shining, which I also love. And then kind of as a segue, psychological books became popular. So The Shining was originally written by Stephen King, who writes these fantastic horror psychological thriller books.

(6:37 – 6:50)

So we obviously had The Shining, and he has over 50 stories that have been turned into movies. So most recently, he’s had It, It Chapter Two, Pet Sematary, Dr. Sleep is coming out here soon. He also has 1922 on Netflix.

(6:51 – 7:15)

But one of his oldest is Cujo, which revolves around a rabid dog that traps a mom and her son in their car during a heat wave, and they’re just trying to survive. When I was in grad school, I had to do these experiments and involved time points. And so I was going in at like 6 p.m., 10 p.m., 2 a.m., 6 a.m., basically every four hours.

(7:16 – 7:36)

On one of these trips, and I was doing this for weeks, and on one of these trips, I was coming back home to my apartment to try to get, you know, a couple of hours of sleep at like 2 a.m. And I encounter this white rat in the parking lot. And I’ve been down, he kind of waddles on over. And I was thinking, oh, this is probably somebody’s pet.

(7:37 – 7:54)

And so I decided to run upstairs and grab a box and bring it back down to see if he would go into it, because I was going to like try to rescue it. And so I lower the box down, and he like waddles on in. And as I’m kind of closing it up, he like jumps out.

(7:55 – 8:11)

And so I lower the box down again, and he kind of waddles over fearlessly and gets back into the box. And as I’m closing it up the second time, he bites my finger deep. And there’s like, I don’t know if you’ve ever had a hand injury, but blood just like rushes out.

(8:11 – 8:21)

There’s like blood streaming out everywhere. So I’m starting to freak out because I was a kind of a new grad student, and we hadn’t like covered rabies yet. Oh, God.

(8:22 – 8:32)

And so I was thinking, oh, my gosh, I’ve just messed up, Dad. And so I’m freaking out. And then the person who would eventually become my wife, she worked in the same lab as me.

(8:33 – 8:45)

We were just friends at the time. And she lived a few buildings over from me. I knew that she volunteered at like vets and with trying to get some like cats and dogs adopted.

(8:45 – 8:51)

So I knew she had like pet carriers. So I call her up in the middle of the night. She actually answers.

(8:52 – 9:00)

That’s her first mistake. She actually answers. And I’m screaming how I need to get this like cat carrier.

(9:00 – 9:16)

If she could please bring me a cat carrier down to my building at 2 a.m. And she shows up and there’s just like blood everywhere. And I’m screaming about this white rat, kind of like, I guess, Captain Ahab with his white whale and Moby Dick. And we never found the white rat.

(9:16 – 9:33)

He just took off. And so I was just terrified, scared to death that maybe I had contracted rabies. And so when I went back to the institution later on, I just like poured through everything to do with rabies and was like asking everybody about rabies.

(9:33 – 9:56)

And it turns out that there’s really no known cases of mice or rats transmitting rabies to people. And one of the reasons is probably because they’re just so small that if a rabbit animal bit a rat or a mouse, they would probably like die. Wasn’t she further along in school than you? Yeah, yeah.

(9:56 – 10:04)

She was like a couple of years ahead of me. So did she not know about the rabies yet either? Oh, she didn’t know what was going on. Oh, oh, you didn’t ask her for help? No.

(10:04 – 10:26)

You just instead bloodied, yelled at this woman to come help you in the middle of the night? Yes. Oh my God. So when most people think about rabies, they think of like cartoons or movies where they’ve seen somebody that is or a dog that’s rabid with the foaming at the mouth.

(10:26 – 10:39)

Rabies is the Latin word for madness, which makes sense. There are two diseases that can occur from rabies. The classic one that most people think of is actually furious rabies.

(10:39 – 11:07)

And they have the hallmark symptoms such as, in addition to feeling bad, the symptoms such as being afraid of water and having difficulty swallowing and just kind of hyper salivating. They also have a lot of agitation and erratic behavior. If you go on YouTube and look for videos of animals or people who have rabies, there’s actually a lot that are improperly labeled, but there are a couple of legitimate videos out there that kind of shows this behavior.

(11:08 – 11:34)

Many of these are from patients that are in India or in Central Africa. These are videos of human patients? They’re not like animals? There’s a couple of them. There’s one in particular that was from a vet that I always show in my classes, and it shows this cat, and the vet opens up the carrier, and the cat at first looked perfectly normal and fine.

(11:35 – 11:55)

And then it starts to leave the carrier, and it has like this drunken appearance to it, this drunken walk to it. And so you can tell maybe it has some neurological problems with it. And then the cat starts to act a little erratically, and the vet has a leather glove on and goes to put his hand near the cat.

(11:56 – 12:08)

And with such impressive speed, the cat strikes out in aggression. So it uses its claws, and it grabs on with its mouth, and it starts to growl. Just like instantaneous? Oh, it’s very fast.

(12:08 – 12:30)

And so these animals, they look drunken and slow, but when it comes time to strike, it’s just impressively fast. So I can understand how millions of people each year are, you know, put themselves at kind of at risk of being bit by a rabid animal. And there are some videos of people too.

(12:31 – 12:50)

The one that always sticks in my mind, it always makes me cry every year, is a video that I think is from CBS News. And they’re doing a story in Angola, and it’s like a children’s clinic. And it’s a story of children that have been infected with rabies.

(12:50 – 13:03)

And it’s just heartbreaking. And you can see all the caretakers there, and they’re all kind of crying. But one of the symptoms of furious rabies is the diaphragm will rapidly go in and out violently.

(13:04 – 13:12)

These very quick movement contractions. And you can see these children, they’re like four years old. And you can see kind of like, you know, their stomach going kind of up and down.

(13:13 – 13:29)

And this video continues and kind of shows how these children became at risk of contracting rabies. And so in the streets of the town they were in, there are just hundreds of just stray dogs. And then there’s just these large groups of children that are being unsupervised.

(13:29 – 13:34)

And so they’re messing with the dogs. Some are trying to pet them. Some are antagonizing them.

(13:34 – 13:50)

And so you have these dogs that are being uncared for that potentially have a disease. And children that are being unsupervised that are in close contact to them. So beyond just rabies, there’s just so many disasters waiting to happen.

(13:51 – 14:20)

And then probably the most telltale sign of rabies is that you have this violent, erratic biting behavior like that we saw in the video of that cat attacking the gloved veterinarian hand. Rabies is caused by a virus that is transmitted, usually through bites that break the skin as the virus is present in nerves in the saliva in the mouth. Transmission can occur between potentially an animal that’s warm-blooded, so particularly mammals and birds.

(14:20 – 14:35)

There have been some lab adaptations that allowed the virus to replicate in the cells of cold-blooded animals though. For birds, the virus doesn’t seem to cause disease and is usually cleared. For mammals, dogs are the leading cause of human infections worldwide.

(14:36 – 14:58)

In the U.S. in particular, the leading causes of infections are from skunks, raccoons, foxes, as well as bats. And had I been more knowledgeable as a young grad student, I would have learned that small mammals such as rats and mice tend not to survive an attack from a rabid animal. And so because of that, there are no known cases of them transmitting the virus to humans.

(14:59 – 15:14)

Human-to-human cases are rare and usually occur through infection during transplantation. Yeah, such as like cornea transplants. Altogether, more than 17,000 people die every year from rabies, with most of those deaths occurring in Africa and Southeast Asia.

(15:15 – 15:34)

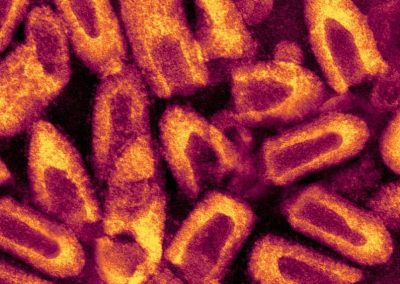

About half of those deaths are from kids years 15 and younger. Yeah, so it is a lot of deaths, but it is a remarkable decrease from even 30 years ago when around 55,000-60,000 people a year were dying from rabies. Rabies virus has a very distinct look to it.

(15:34 – 15:55)

It looks a lot like a bullet with a cylindrical shape that becomes tapered on one end, kind of like a cone-like end on one side. After a bite, the rabies virus can attach to the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on muscle cells. So those receptors are just the primary receptors responsible for muscle contraction within muscles.

(15:55 – 16:31)

After replicating in muscle cells, the virus is able to cross the synaptic cleft, which is that gap between the muscle cell and the motor neuron cell, and can bind to the neural cell adhesion molecule, also known as NCAMs, on neuronal cells. The virions then travel in a retrograde direction within the axons. The axons are going to be the long part of a nerve cell, and they move at a remarkably slow rate of less than half an inch a day to at most 15 inches per day.

(16:31 – 16:52)

And this slow movement of the virus up the central nervous system is going to be important to remember when we talk about treatments later. The virus then replicates in the motor neurons and eventually reaches the brain, and it will also migrate to the salivary glands. We’ve known about rabies for a long time.

(16:52 – 17:10)

There are some legal documents from 2300 BC in Mesopotamia, in which there was, I guess, almost like a lawsuit. And there was a guy that got bit by a rabid dog and he died. And the courts determined that the owner of the dog had to pay like this massive fine.

(17:11 – 17:41)

We also have records from Hippocrates around 400 BC, Aristotle around 350 BC, Democritus around 400 BC, and Pliny in the 1st century. There have been a number of ineffective treatments invented throughout those times. I think the most intense one occurred throughout the Middle Ages, around the 5th through the 15th century.

(17:41 – 18:03)

These monks would keep this large spike or nail that’s kind of ornamental on one end, and it’s called the St. Hubert’s key. And what they would do was they would heat this thing up red hot. And if you were bit by an animal, they would try to cauterize the wound with this extremely hot metal spike.

(18:04 – 18:21)

And also, I guess, for luck, they would also try to brand dogs and other animals to try to ward off them getting the virus. Of course, that didn’t really work either. The big breakthrough treatment for rabies came in 1886 from Louis Pasteur and his collaborator, Émile Roux.

(18:21 – 18:38)

So most people know Pasteur for his process in heating up milk to kill bacteria, which is what the pasteurized label on your milk means. But he had a number of significant contributions, one of the most important being creating the first rabies vaccine. So up until this vaccine was made, rabies was essentially an incurable and fatal disease.

(18:39 – 19:01)

Pasteur and team took the nerves of infected rabbits and dried them out to make a killed inactivated vaccine. And he first tested this vaccine out on 50 dogs, and then on a nine-year-old boy named Joseph Meister, who received 13 painful shots to the abdomen over an 11-day period. Yeah, this was kind of controversial move on Pasteur’s part, because he was not a medical doctor.

(19:02 – 19:26)

But Pasteur was so famous at the time, I think a lot of people gave him a free pass, because he was like this amazing genius wizard. Meister was the first of many hundreds to receive the vaccine over the next year, and this was the beginning of what is now the famous Pasteur Institutes in Paris. Joseph worked as a caretaker in the Pasteur Institute later on as an adult, all the way until his death in 1940.

(19:27 – 19:56)

While this seems like it’s a happy ending, it actually isn’t. When he was 60 years old in 1940, the Nazis invaded France and Paris, and he had sent his family away to try to save them from the invading army. And overwhelmed with guilt of not knowing like what happened to them, Joseph actually committed suicide right before his family returned to Paris.

(19:56 – 20:12)

Later on that same day. I remember my mom used to threaten me when I was a kid from going out into the woods and like touching animals. She would tell me I would have to get those 13 painful shots in my stomach.

(20:12 – 20:32)

So it’s kind of like this old wives tale. The modern vaccine isn’t like that now, it’s different. So instead you receive one shot of an anti-rabies antibody, and then four vaccine shots near the bite site, with the remainder injected on your back shoulder over two week periods that you maintain your own antibodies.

(20:33 – 20:51)

What’s different from this vaccine as compared to many others is that you get it after you encounter the virus, so post-exposure prophylaxis. Altogether about 50 million people are treated this way each year. The reason that this works for this virus is that the rabies virus takes so long to travel up its way from the entry site and up the axon of the nerves to the brain.

(20:52 – 21:06)

And so it’s important to get the vaccine after you get bit, but it’s also important that you do it right away before symptoms occur. Yeah, you need to do it right away and before symptoms occur. That can’t be underlined enough.

(21:07 – 21:28)

In all of human record, there are only about 15 people who have survived rabies after developing symptoms. And you said how many people are dying a year from this? Yes. No, how many? Like 15 million? No, about 17,500 now.

(21:28 – 21:36)

17,500 people a year are dying from this. And even with that much occurring every year, only 15 people total have survived. Yes, it used to be much higher.

(21:37 – 21:45)

I mean, it used to be hundreds of thousands of people, not more than that. This is almost essentially 100% fatal disease once symptoms occur. Yeah.

(21:46 – 22:06)

Probably the most well-known case of somebody surviving rabies after symptoms have occurred was a case involving a young woman named Gina. And she underwent what is now known as the Milwaukee Protocol. And so what’s interesting about rabies is it doesn’t actually damage the neurons.

(22:07 – 22:20)

And so the physicians put her into a medically induced coma and then tried some antivirals on her. And then she actually did survive. And she has a YouTube channel.

(22:20 – 22:40)

So you actually go and watch some videos of her talking about her experience. So Gina Geis. Another modern vaccination strategy is to put vaccines in these bait pellets and then fire them out of a gun on an airplane.

(22:41 – 22:57)

What? Yeah, it’s awesome. If I could have another job, it would be this job. So it’s like those crazy scenes in movies where they have this machine gun thing and they’re looking at helicopters shooting into a forest? Yes.

(22:58 – 23:06)

Yes. So there’s a gun-like apparatus. And then the bait strips are held together kind of like when you see machine guns and all the bullets are linked together.

(23:06 – 23:12)

So the bait strips look like that. And they fire it out of a Cessna over wooded areas. OK.

(23:12 – 23:19)

All right. And then the bait strips, they obviously go to the ground and the animals eat them and they get vaccinated that way. Yes, that’s correct.

(23:19 – 23:31)

So we’re actually vaccinating wild animals. And between the United States and Canada, we fire out about 10 million of these vaccine bait balls. Per year? Per year.

(23:32 – 23:54)

That’s an impressive amount. So to recap, we talked about gothic fiction with Edgar Allan Poe, the progression of horror stories, the prolific nature of Stephen King, including Cujo and its pop culture introduction to rabies, and the post-exposure vaccine strategy. Thank you for listening to episode 8, Rabies Day Out.

(23:54 – 24:10)

Show notes, transcripts, citations, and social media links are available on our website at germanwix.com. So I think most people have some kind of horror movie that scarred them in some sense. Mine was The Ring. So the static TVs, to this day, still make me uncomfortable.

(24:10 – 24:20)

If a TV gets static, I’ll just straight up leave a room without explanation. I don’t care to explain myself for that. My mom’s was The Bird, obviously directed by Alfred Hitchcock.

(24:20 – 24:34)

And so to this day, if she sees birds on power lines, she gets uncomfortable. When I was five years old, she would hold my hand while we were leaving Walmart because all the birds, as if I would make some kind of difference at five years old. The movie that scarred my life was Poltergeist.

(24:34 – 24:48)

And I could not sleep in my room without staring at the closet door until I eventually passed out. I still hate closets. I think that’s actually really funny.

(24:48 – 25:04)

The other funny one that I know is my aunt, who lives in Kansas in like the middle of like farm country, like this corn country, right? When she was growing up, she watched Children of the Corn. And even now she’s like in her 50s. And she is terrified of like corn stalks at night.

(25:04 – 25:11)

She’s just like horrified of them. But she lives in the middle of corn, like her house is surrounded by cornfields. So she just like won’t go outside at night by herself.

(25:12 – 25:21)

She’s lived in this house for like over 20 years now. She won’t go outside by herself because she’s so afraid of this corn. After like 30, 40 years since she’s seen this movie.

(25:21 – 25:24)

She won’t move. She won’t move. Yeah, I know.

(25:24 – 25:26)

They love that house. It’s just the corn.

Credits

Written and performed by Dr. Dustin Edwards and Faith Cox

Music from https://filmmusic.io

“Graveyard Shift“, “Day of Chaos“, “Distant Tension” by Kevin MacLeod (https://incompetech.com);

license CC BY 4.0

“Toccata et Fugue” by Johann Sebastian Bach; public domain

“Also Sprach Zarathustra” by Richard Strauss; license CC BY 3.0

“Thunder” by Mike Koenig; license CC BY 3.0

“Godzilla” public domain

Images from

Edgar Allen Poe circa 1849; public domain

rabies virus © Frederick Murphy, UTMB; public domain